“Corporate taxation has declined since the 1980s”

Big multinational companies—and their shareholders—have been the main winners from globalization: their profits have boomed thanks to the ever-closer integration of world markets. A lot more can and should be done in order to ensure that these actors pay their fair share of taxes. We discuss in this chapter why increasing the global minimum corporate tax rate beyond 15% matters from an economic point of view.

The role of corporate tax in the progressivity of the tax system

Along with the wealth tax, the taxation of multinationals has attracted a lot of attention in recent years. This is hardly surprising: billionaires and multinationals are the most powerful economic actors globally, and have become even more prosperous in the post-Covid world. So much so that it is hard to think of changing the global economic system without a major reform of taxation for both high wealth individuals and large multinational corporations. Unfortunately, these two discussions are often dealt with separately. We believe that it is important to link them up in a more systematic manner than what is usually done.

Generally speaking, corporate tax contributes to the progressivity of the tax system because it is a tax on corporate profits, and corporate profits tend to be concentrated at the top of the income distribution. As such, increasing the corporate income tax rate can increase the progressivity of the overall tax system. To think about this more accurately, several considerations need to be taken into account.

Firstly, corporate tax is a relatively blunt instrument to increase tax progressivity, because it is typically levied at a flat rate. In other words, a profit of €1 billion is taxed at the same rate as a profit of €1 million. In theory, corporate profits could be subject to a progressive tax rate schedule, with higher rates applying to larger profits. The main practical obstacle to this policy is that this would incentivize corporations to split in order to avoid the higher tax brackets. Furthermore, owners of very large businesses are not always richer than owners of smaller businesses. For example, pension funds for the middle-class own parts of the largest businesses whose shares are publicly traded, while smaller start-ups are privately owned by very wealthy founders or venture capitalists. For that reason, although some countries apply lower rates to small corporations, in many countries all corporate profits are subject to the same rate.

Secondly, not all business profits are subject to corporate tax. Some businesses are taxed at the individual level: their profits, exempt from corporate tax, are allocated to shareholders and subject to the progressive personal income tax schedule. This is the case for partnerships and S-corporations in the United States and for business partnerships in Germany, for example. The more profits are taxed at the individual level, the less powerful corporate tax, as an instrument for affecting the progressivity of the tax system, becomes (while personal income tax becomes a more powerful instrument).

Thirdly, the current progressivity of corporate tax system depends on the concentration of equity wealth, which varies across countries and over time depending on the development of wealth inequality. More wealth inequality is typically associated with more concentrated equity ownership. For a given level of overall wealth inequality, equity wealth can be less concentrated in countries with broad-based pension funds than in countries with pay-as- you-go pension systems.

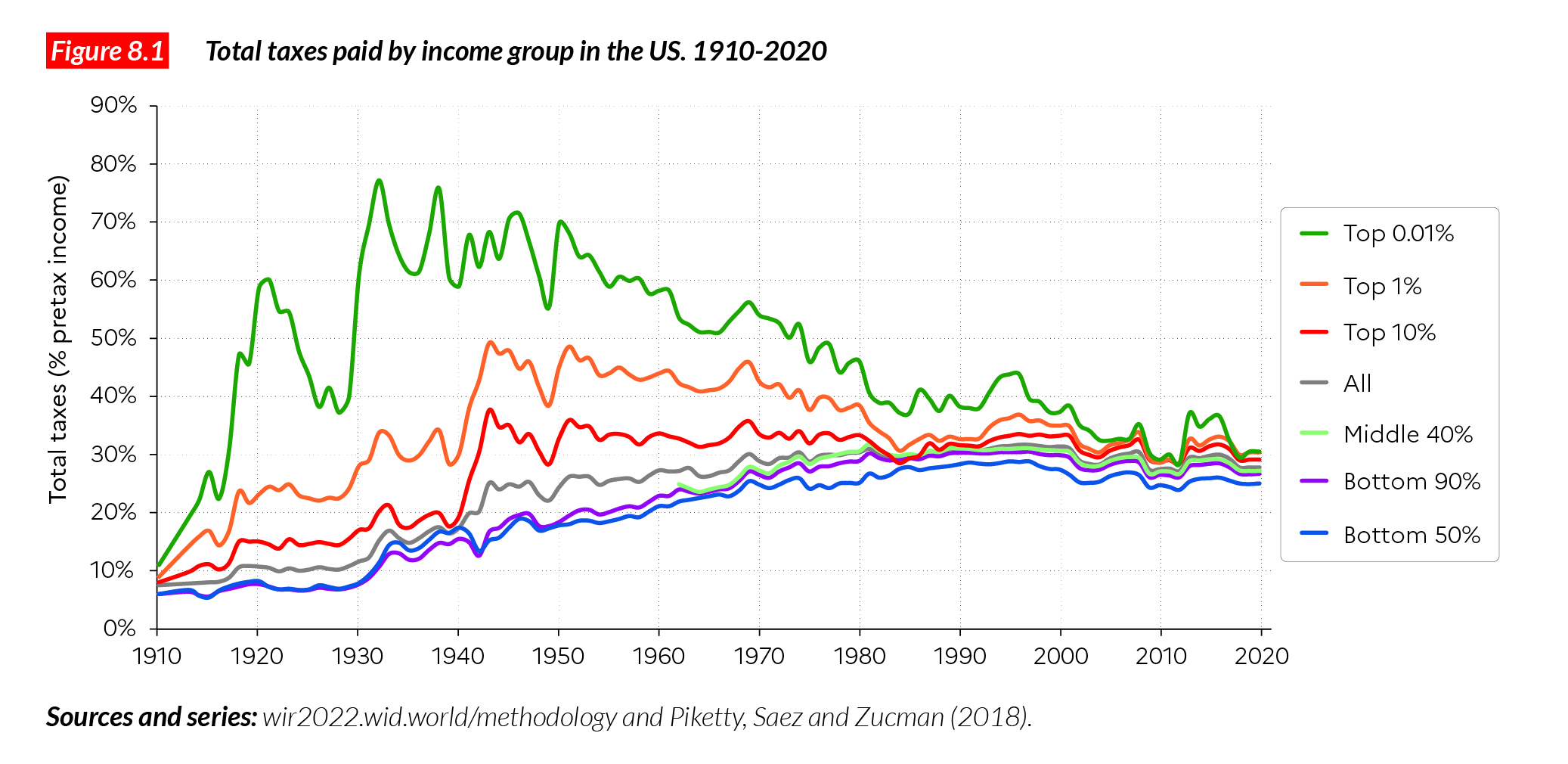

Figure 8.1 illustrates the overall tax progressivity in the United States between 1910 and 2020. It shows that the effective tax rate of the top 1% and top 0,01% of individuals rose steeply between 1910 and 1940 and remained significantly above that of other groups of the population until the 1970s-1980s and dropped significantly afterwards. Over the course of the 20th century, total taxes paid by poorer groups increased. Today, the effective tax rates of the working class, the middle class and top 1% are very close. As a matter of fact, the decline of corporate taxation played an important role in the strong decline of overall tax progressivity in the US.

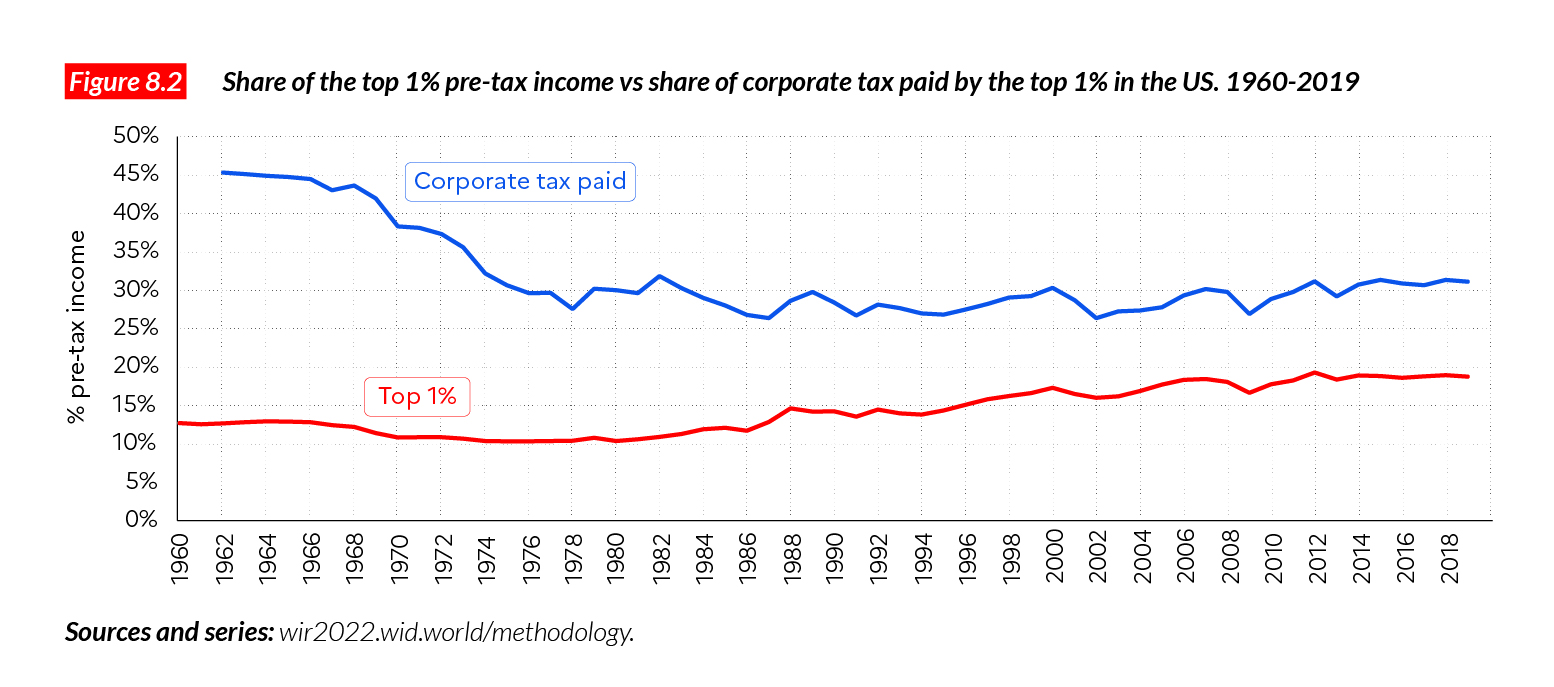

Figure 8.2 illustrates the progressivity of the corporate tax system in the United States. Let us note that the US is one of the very few countries in which estimates for the joint distribution of income and equity wealth are available1. Adults in the top 1% in the highest pre-tax income bracket earned 19% of total U.S. pre-tax income in 2019. They also owned about 30% of the equity wealth of corporations subject to corporate tax, including equities held through pension funds. Therefore, corporate tax, although levied at a flat rate, was progressive. Moreover, as shown by Saez and Zucman2, corporate taxes are on average more progressive than other U.S. taxes. While the top 1% paid about 30% of the corporate tax, they paid around 21% of all taxes (federal, state, and local) in 2020. This means that an increase in the taxation of corporate profits would introduce greater progressivity in the U.S. tax system.

Figure 8.2 also shows that the U.S. corporate tax was more progressive in the 1960s, when equity wealth was even more concentrated than it actually is today, before the rise in pension funds somewhat broadened equity ownership.

Finally—and perhaps most importantly— corporate tax matters for the progressivity of the tax system as it prevents wealthy individuals from avoiding paying progressive personal income tax. Progressive personal income tax cannot function properly when corporate tax rates are too low: in such case, high-income people can incorporate to report their income through their personal companies (subject to low corporate tax rate) rather than in their individual capacity (subject to high personal income tax rate). This is the reason why in most high-income countries, corporate income tax was born around the same time as personal income tax, in most cases just before or during World War I3, Although it also comes to serve other purposes—for instance, ensuring that companies contribute to funding the infrastructure they benefit from — corporate tax is consequently fundamentally a backstop: it prevents wealthy individuals from shielding their income from taxation by pretending this income has been earned by a firm.

In sum, corporate tax and personal income tax are supplements. It is hard to have a highly progressive income tax system without a high enough corporate tax. “Taxing corporations” is not a substitute for “taxing wealthy individuals”, but a requirement to do so effectively.

The decline in corporate taxation since the 1980s

One of the most striking developments in global tax policy since the 1980s has been the decline in corporate income tax rates. Between 1985 and 2018, the global average statutory corporate tax rate fell by more than half, from 49% to 24%4. This trend shows no sign of abating. Since 2013, Japan has cut its rate from 40% to 31%; the United States from 35% to 21%; Italy from 31% to 24%; Hungary from 19% to 9%; a number of Eastern European states are following suit.

Effective corporate income tax rates have also declined, albeit slightly less so. According to recent estimates5, the global effective average corporate tax rate fell from close to 30% in the 1960s to about 25% in the 1980s and 18% in 2020. The decline was less dramatic than the fall in statutory rates, because of the decline in interest payments (which are deductible from the corporate tax base) and other changes in the tax base. The decline was concentrated in high-income countries. In the United States, for example, the U.S. (federal plus state) effective corporate tax rate on U.S. corporations’ profits (for corporations subject to corporate income tax) was halved between 1980 (28%) and 2020 (14%).

This development raises issues. Firstly, it reduces government revenue at a time of growing public deficits and declining public wealth. Secondly, it erodes the progressivity of the tax system. Thirdly, and most importantly, it undermines the sustainability of progressive income taxation. With the decline in corporate tax rates, incorporating is becoming more valuable for high-income individuals. Once they operate as corporations, high-income individuals6 can shift income from personal income tax to corporate tax. Examples of such shifting abound throughout the world, from Israel to Sweden. Norway or Finland7.8.9.10.

The main difference between available historical record and today’s situation is that until recently, governments were often careful to limit the gap between top income tax rates and corporate taxes. With the accelerated decline of corporate taxation globally, this gap is increasing and putting new pressure on the personal income tax system. If policymakers want to maintain progressive income taxation, it is essential to stop the ‘race to the bottom’ regarding corporate tax rates and increase effective taxation of corporate profits.

The promises and pitfalls of minimum taxation

In June 2021, more than 130 countries and jurisdictions agreed that multinational profits would be subject to a minimum tax of 15%11.

Such an agreement—whose details have not yet been finalized—would mark a milestone, because it would be the first international agreement establishing a limit on how low tax rates can go. Since the end of the 1990s and under the auspices of the OECD, high- income countries have signed agreements to harmonize their tax bases. The Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) process, launched in 2015, tries to achieve a harmonized definition and allocation of taxable profits across countries to prevent some forms of corporate tax avoidance, such as breaching double tax treaties (and inconsistencies therein). But countries face no limits in how they set rates. Any rate, even 0%, is acceptable.

An agreement on minimum taxation would change such situation. Countries in which multinational companies are headquartered could collect a tax on profits made by their subsidiaries to ensure that profits are taxed at an effective rate of at least 15% on a country-by-country basis. For example, if the Irish subsidiary of a French multinational has an effective tax rate of 10% in Ireland, then France could collect a tax of 5% to reach a rate of 15%; if a subsidiary has an effective rate of 0% in Bermuda. France could collect a tax of 15% on the profits booked in Bermuda. Other countries could proceed similarly with their own multinationals. Estimates of such minimum tax levied by countries were produced for the US12 and European Union countries13.

If well implemented, a minimum tax of this kind would remove incentives for countries to offer rates lower than 15%, since these low rates would be offset by additional taxes owed in the parent country. This would alleviate some of the most extreme forms of tax competition such as some countries choosing to offer zero statutory rates and zero effective tax rates. Existing estimates suggest that about 36% of multinational profits are transfered to tax havens each year14.

However, the agreement is also flawed in several key aspects. Firstly, the rate—15%—is lower than what working-class and middle- class people typically pay in high-income countries. It is also lower than the average statutory rate that corporations face in those places. There is a risk that such a low reference point might trigger an additional reduction in statutory corporate tax rates in the countries that currently apply higher rates, thus reinforcing the ‘race to the bottom’ with corporate taxation observed since the 1980s. A higher rate (of 25%, for example) would reduce the risk of such a counterproductive outcome.

Secondly, the draft agreement includes carve- outs allowing corporations with sufficient activity in low-tax countries to be exempt from the minimum tax. Specifically, the proposed agreement allows multinationals to reduce profits subject to the minimum tax by an amount equal to 5% of the value of their assets and labor costs in each country. In theory, a minimum tax with no substance carve-out means that some tax rates are considered too low by the international community. A minimum tax with carve-outs, by contrast, reflects a different perspective. With such a tax, a company that owns

€1 billion in assets in a country with a 0% corporate tax rate, and makes €50 million in profit in the afore-mentioned country, could still be exempt from taxes. Thus, a minimum tax with carve-outs for capital and employment does not address the ‘race to the bottom’ in corporate taxation. Worse still, it incentivizes firms to move capital and employment to places where tax rates are very low, to avoid paying the minimum tax15.

Thirdly, the agreement includes a provision that allows corporations to challenge the determination with which countries say they should pay taxes through a secretive arbitration system16, Decades of investment arbitrations have demonstrated that “who decide” can be even more important than the written rules themselves. Arbitrators, acting out of the public eye and paid on a case-by- case basis, will have incentives to interpret the new rules in ways that favor corporations and generate future cases for them to arbitrate. If it is deemed necessary to have some type of legal mechanism to resolve international tax disputes, it is preferable to build on the international public law system with tenured judges in the fields of trade and human rights.

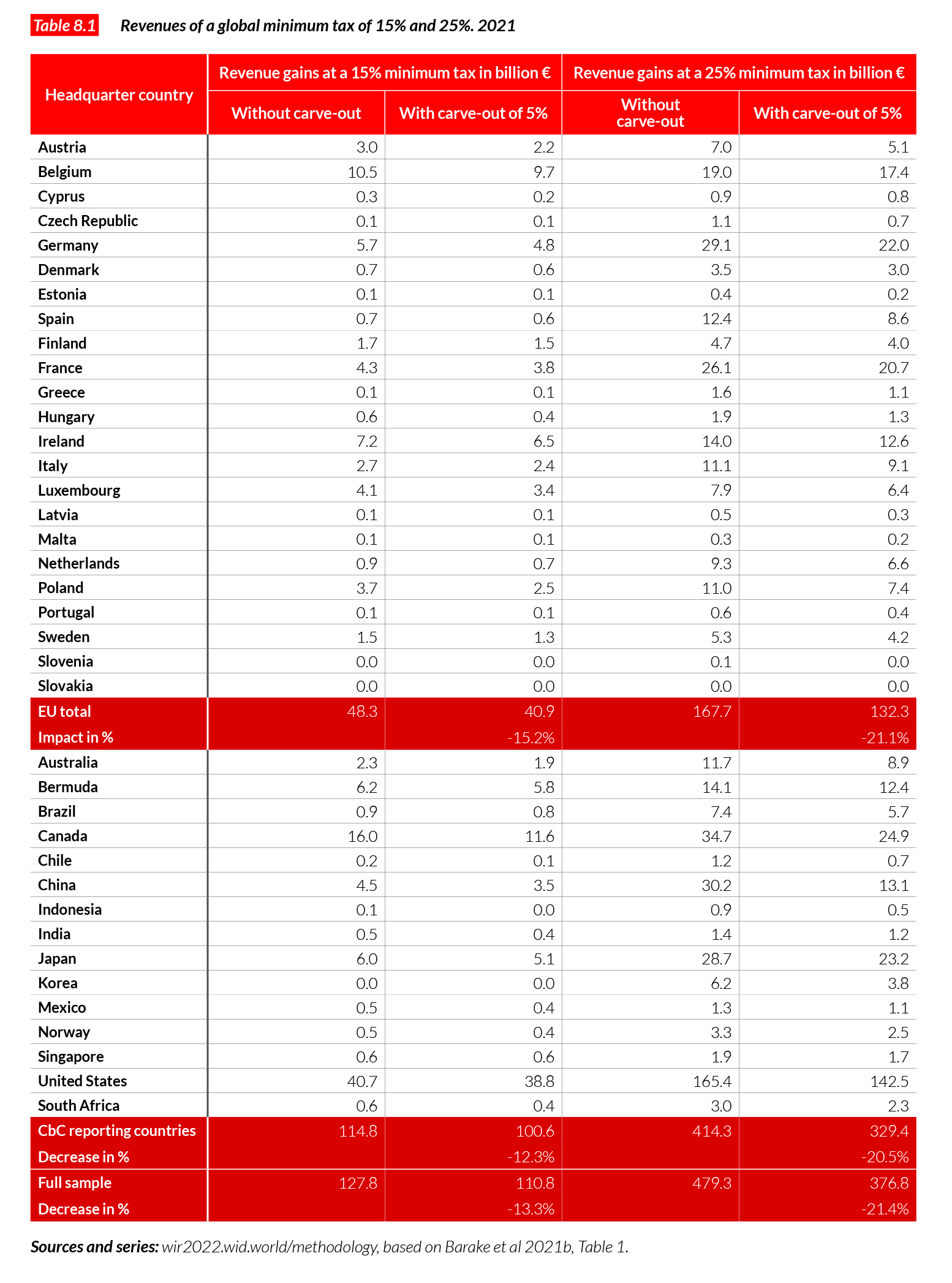

Some of these flaws could be addressed by increasing the minimum tax rate and simplifying the proposal, so that it applies to all profits (with no exemption for substance or any other reasons). Table 8.1 shows simulations of how much revenue each EU country and several non-EU countries (including large developing countries such as China) could collect for two minimum tax rates (15% vs. 25%), with and without carve- outs for substance17. Among the countries considered, a 25% minimum tax without carve-out could generate four times more revenue than the current OECD-led proposal of 15% with carve-outs: €479 billion per year, as opposed to €111 billion. The table also shows the negative effects of carve-outs introduction, especially as one considers higher rates than 15%. A 25% minimum tax with carve-outs generates 21% less revenue than the same tax without carve-outs.

Big multinational companies—and their shareholders—have been the main winners from globalization: their profits have boomed thanks to the ever-closer integration of world markets. As their activity rose, so did their power and influence; for some of the largest multinationals, this power now rivals that of nation-states. Asking multinational firms to pay €128 billion more in taxes annually when they could pay €479 billion more (with a 25% rate, which would remain low from a historical perspective) is a policy and a political choice which need to be democratically and transparently debated.

1 Piketty. T.. E. Saez and G. Zucman. 2018. “Distributional National Accounts: Methods and Estimates for the United States.” Quarterly Journal of Economics. 133(2). 553–609.

2 Saez. E. and G. Zucman. 2021. “A Wealth Tax on Corporations’ Stock”. working paper.

3 Zucman. G. 2014. “Taxing across borders: Tracking personal wealth and corporate profits.” Journal of economic perspectives 28. no. 4: 121-48.

4 Tørsløv. T. R.. L. S. Wier. and G. Zucman. 2018. “The missing profits of nations.” National Bureau of Economic Research. No. w24701.

5 Bachas. P.. A. Jensen. M. Fisher-Post and G. Zucman. 2021. “Globalization and Factor Income Taxation.” working paper.

6 Saez. E. and G. Zucman. 2019. The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make them Pay. New York: W. W. Norton.

7 Romanov. D. 2006. “The Corporation as a Tax Shelter: Evidence from Recent Israeli Tax Changes.” Journal of Public Economics 90. no. 10–11: 1939–1954.

8 Edmark. K. and R H. Gordon. 2013. “The Choice of Organizational Form by Closely-Held Firms in Sweden: Tax Versus Non-Tax Determinants.” Industrial and Corporate Change 22. no. 1: 219–243.

9 Alstadsæter. A. 2010. “Small Corporations Income Shifting Through Choice of Ownership Structure—A Norwegian Case.” Finnish Economic Papers 23. no. 2: 73–87.

10 Pirttilä. J.. and H. Selin. 2011. “Income Shifting within a Dual Income Tax System: Evidence from the Finnish Tax Reform of 1993.” Scandinavian Journal of Economics 113. no. 1: 120–144.

11 OECD. 2021. “Statement on a Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising From the Digitalisation of the Economy”. https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/statement-on-a-two-pillar-solution-to-address-the-tax-challenges-arising-from-the-digitalisation-of-the-economy-july-2021.pdf

12 Clausing. K.. E. Saez. and G. Zucman. 2021. “Ending Corporate Tax Avoidance and Tax Competition: A Plan to Collect the Tax Deficit of Multinationals.” working paper. UC Berkeley and UCLA.

13 Baraké. M.. P.-E. Chouc. T. Neef and G. Zucman. 2021a. “Collecting the Tax Deficit of Multinational Companies: Simulations for the European Union.” EU Tax Observatory Report n°1.

14 Tørsløv. Wier. and Zucman. “The missing profits of nations.”

15 Baraké. M.. P.-E. Chouc. T. Neef and G. Zucman. 2021b. “Minimizing the Minimum Tax? The Critical Effect of Substance Carve-Outs.” EU Tax Observatory Note.

16 Tucker. T. N.. J. E. Stiglitz and G. Zucman. September 2021. “Ending the Race to the Bottom”. Foreign Affairs.

17 The table is taken from Baraké. Chouc. Neef and Zucman. “Minimizing the Minimum Tax?