“Modernizing our tax systems to address 21st century challenges”.

Over the last decade, there has been progress in some areas of international tax cooperation: more information sharing among countries, and steps towards a fight against the most aggressive forms of tax competition have been taken. However, more ambitious measures—such as a minimum tax on multinational profits, a transnational tax on the very wealthy, or a global carbon tax—may take a long time to materialize. In that context, it is useful to ask what can be done unilaterally by individual countries and how useful such unilateral initiatives can be.

To regulate inequality and address the revenue needs arising from the Covid-19 pandemic, climate change, and public investment (in healthcare, education, and infrastructure), international cooperation is paramount. Over the last decade, there has been progress in some areas of international tax cooperation: more information sharing among countries, and steps towards a fight against the most aggressive forms of tax competition (see Chapter 8) have been taken. However, more ambitious measures—such as a minimum tax on multinational profits, a transnational tax on the very wealthy, or a global carbon tax—may take a long time to materialize. In that context, it is useful to ask what can be done unilaterally by individual countries and how useful such unilateral initiatives can be. It is also critical to design better indicators in order to be able to assess progress in favor of tax justice (or the lack thereof).

Usefulness of unilateral approaches: the case of FATCA

A good example of how useful unilateral approaches can be is given by the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA). For a long time, the notion that offshore tax evasion could be dealt with effectively was viewed with caution. If some countries want to apply strict bank secrecy rules, aren’t they entitled to do so, and what could make them review their policies? This changed in 2010, when the United States unilaterally enacted FATCA, which imposes an automatic exchange of data between foreign banks and the US tax authority. Financial institutions throughout the world must identify who, among their clients, are American taxpayers and tell the Internal Revenue Services (IRS) what each person has on their bank accounts and what their income earned is. Failure to take part in this program carries stiff economic sanctions: a 30% tax on all dividends and interest income paid to the uncooperative financial institutions, collected by the US1.

This threat has proven effective in securing (formal) cooperation from most of the world’s tax havens and financial institutions. Countries such as Switzerland which had refused for decades to send bank information to foreign tax authorities quickly started to do so. Almost overnight, bank secrecy, which had been depicted as immortal, was abolished – at least partly. Some large countries were initially skeptical and there are still some visible cracks in the system nowadays, but by and large, the 30% withholding tax has served as a sufficiently powerful deterrent.

This U.S. initiative paved the way for key developments in tax information sharing across the globe. In 2011, the European Union adopted its own version of FATCA, known as DAC (Directive on Administrative Co-operation). Most importantly, the OECD developed the Common Reporting Standards (CRS) in 2014. The CRS sets out guidelines and procedures for countries to share financial and tax information in a standardized and automatic manner. This is the key novelty of the CRS: an exchange of information between countries absent prior suspicion of fraud by tax administrations. Automatically accessing standardized tax data from other countries is essential for tax authorities, as international requests can otherwise take up to several months or years to be processed—when processed at all. Under CRS, participants must automatically provide information, such as taxpayers’ identification, account numbers, account value, and income earned.

The CRS was adopted by more than 100 countries and started to be implemented in 2017 and 2018. Main tax havens, including Luxembourg, Singapore, and the Cayman Islands, are now part of this new form of cooperation. Automatic sharing of bank information has therefore become an global standard. in that respect, unilateral action from one large country eventually led to the emergence of a new form of international cooperation while it was still regarded as a utopian idea ten years ago.

As detailed below, this framework still has loopholes. The lack of information provided by countries makes it impossible to provide a thorough assessment of the CRS effectiveness so far. Furthermore, there is a lack of controls and sanctions for non- compliant financial institutions. It would be naïve to believe that the same institutions, which facilitated tax fraud for decades— sometimes taking extreme steps such as smuggling diamonds in toothpaste tubes or handing out bank statements concealed in sports magazines2—are now in all honestly cooperating with global tax authorities. There is also an incentive problem: facilitating tax evasion can generate substantial revenue for some legal and financial intermediaries. Besides, there is also an information problem. Due to financial opacity, it has become easy for wealthy tax evaders to disconnect themselves from their assets, by using trusts, foundations, shell companies, and other intermediaries. Although the CRS mandates financial institutions to look into these intermediaries to identify beneficial owners and forward that information to the relevant tax authority, it remains unclear whether these rules are well applied in practice.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the automatic exchange of bank information marks a major positive break with earlier practices. Before the Great Recession of 2008-2009, hardly any data was exchanged between banks in tax havens and other countries’ tax authorities. Hiding wealth abroad, in that context, was easy. Doing so nowadays requires a higher degree of sophistication and determination. The experience of FATCA suggests that unilateral action can make transformative forms of coordination emerge in a relatively short time span.

Estimates of unilateral vs. multilateral tax deficit collection

Could the experience of FATCA be replicated to address corporate profit shift to tax havens? Saez and Zucman3 discuss how a country can unilaterally collect multinational tax deficit—defined as the difference between what this multinational currently pays in taxes, and what it would have to pay if it were subject to minimum effective taxation in each country where it operates. Baraké and co-authors4 discuss various ways for EU countries to collect multinational tax deficit, ranging from a perfect international tax cooperation to unilateral action. The following, adapted from Baraké and co- authors5, clarifies the implications of such scenarios within the EU framework.

To start with, Baraké and co-authors6 consider a global agreement on a minimum tax of the sort, as currently being discussed by the OECD (see Chapter 8). In this scenario, each EU country collects its own multinationals’ tax deficit. For instance, if the internationally agreed minimum tax rate is 25% and a German company has an effective tax rate of 10% on the profits it records in Singapore, Germany would then impose an additional tax of 15% on such profits to reach an effective rate of 25%. More generally, Germany would collect extra taxes so that its multinationals pay at least 25% in taxes on the profits they book in each country. Other nations would proceed similarly. Such a minimum tax of 25% would have increased corporate income tax revenue in the European Union by about €170 billion in 2021. This sum accounts for more than half of the total corporate tax revenue currently collected in the European Union and 12% of total EU healthcare spending.

Secondly, Baraké and co-authors7 posit an incomplete international agreement in which only EU countries apply a minimum tax, while non-EU countries do not change their tax policies. In this scenario, each EU country collects its own multinationals’ tax deficit (like in the first scenario), as well as a portion of the tax deficit of multinationals incorporated outside of the European Union, based on the destination of sales. For example, if a British company makes 20% of its sales in Germany, Germany would then collect 20% of this company’s tax deficit. In such a scenario, using a 25% rate to compute each multinational’s tax deficit would mean that the European Union would increase its corporate tax revenues by about €200 billion. Out of this total, €170 billion would come from collecting EU multinationals tax deficit; an additional €30 billion would come from collecting a portion of non-EU multinationals tax deficit.

Lastly, Baraké and co-authors8 estimate how much revenue each EU country could unilaterally collect, assuming all other countries keep their current tax policy unchanged. This corresponds to a “first mover” scenario, in which one country alone decides to collect multinational companies’ tax deficit. The first mover would collect the full tax deficit of its own multinationals, plus a portion (proportional to the destination of sales) of the tax deficit of all foreign multinationals, based on a reference rate of 25%. A first mover in the European Union would increase corporate tax revenue by close to 70% compared to current corporate tax collection. Acting as a “first mover” can yield substantial tax revenue. Of course, a unilateral approach would incentivize existing companies to change nationality— so-called corporate inversions. However, countries have a considerable degree of discretion when defining corporate nationality. A unilateral move would need to go hand in hand with a tightening of regulations to prevent companies from changing nationality.

This analysis has two major implications. First of all, although international coordination is always preferable, a unilateral move from a single state (or a group of states) would push other EU countries to also collect multinationals’ tax deficit—since not doing so would be tantamount to leaving tax revenue on the table for first movers to grab. This could pave the way for an ambitious agreement on a high minimum tax within the European Union, and then globally. Unilateral action can play a transformative role, by triggering a “race to the top” in which more and more countries act as “last resort tax collectors” and collect multinational companies tax deficit. A similar approach could be developed to collect billionaires’ tax deficit, combining bold transparency requirements and high wealth taxes.

Secondly, refusing international coordination is unlikely to be a sustainable solution, because other countries can always choose to collect taxes that tax havens choose not to collect. This means that the development strategy of tax havens, predicated on low- tax rates, may be unstable. Tax competition is a political choice. Since high-tax countries tend to lose tax revenue, capital, and employment because of tax competition, it is not impossible that some of these countries may try to make different choices—such as unilaterally taxing profits booked in tax havens—in the future. This would make it less financially rewarding for multinational companies to book profits in tax havens, making it in turn less beneficial to tax havens themselves to offer low rates.

What this requires, however, is a stronger political will to curb tax evasion and promote tax justice than what has been observed until now. In particular, individual countries in Europe would need to take unilateral actions, while also recommending an ambitious framework for international cooperation with other countries. Without unilateral action, it is hard to see how the European Union (and the world) will be able to escape the “unanimity trap” which was put in place in the past.

Anti-tax evasion schemes contain many loopholes and cannot be assessed

Together with multinationals’ taxation, there has been ample discussion in recent years about global tax evasion and the lack of financial transparency around cross-border financial assets. Following the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent high profile tax evasion “stories”, governments around the world and international organizations claimed that they had made significant progress in the fight against tax evasion. Before the financial crisis of 2008, tax havens typically refused to share any information with foreign tax authorities. Since then, several reforms have been initiated and contributed to changing the rules of the game as regards to the transfer of information between countries. They either took the form of unilateral processes (eg. FATCA) or multilateral ones (eg. CRS, see above).

By 2020, 107 countries took part in the CRS, including notable tax havens (such as Switzerland). The total amount of assets reported in 2019 reached $11.2 trillion, with 84 million accounts reported. As a comparison, the estimated amount of missing portfolio liabilities was $4.5 trillion in the early 2010s9. These developments have led the OECD and several news organizations worldwide to trumpet the “end of bank secrecy”10. Unfortunately, the reality is not as bright.

Today, tax evaders can bypass the CRS in at least three different ways: investing in non- participatory countries, investing in countries with a low rate of CRS enforcement, or investing in bodies that are not subject to reporting.

Firstly, not all countries have agreed to the CRS. As of now, most African countries as well as the USA are not part of this exchange of information . It is worth mentioning that the USA, despite having cracked down on other tax havens over the past few years, and despite FATCA, ranks second in the Financial Secrecy Index11 (after the Cayman Islands and ahead of Switzerland). As a matter of fact, the USA hosts tax havens, such as Delaware, Nevada and Wyoming. Recent research has shown that the CRS is likely to have increased the level of cross-border deposits in the USA compared to other countries. A possible explanation is that the use of shell companies incorporated in the USA has increased after the CRS12 was introduced13.

Secondly, several countries, which have signed the CRS, are poorly equipped to properly enforce it and to make sure that banks and financial institutions properly report information to tax authorities. Overall, non-compliance with CRS standards remains difficult to monitor nowadays and threats of sanctions appear to be limited.

Thirdly, some institutions or assets are still not subject to reporting requirements. This mechanism has been improved since 2014 to fill some of the loopholes, but participating countries can still decide to exclude certain institutions from the list (if these are not likely to participate in tax evasion, but this assessment largely depends on the country’s commitment to seriously do so).

Bearing these limitations in mind, we would like to stress that the CRS does represent an improvement from the pre-2010 situation and shows that multilateral cooperation is possible in tax matters. The main issue with the CRS is that it is impossible for independent observers to assess how large or how small these improvements have been, because tax authorities do not disclose the information required to properly track basic progress towards tax justice.

Properly assessing the road towards tax transparency: publishing basic information

If the exchange of information across countries as per the CRS or FATCA were effective, tax authorities across the globe should then be in a position to release key information about their residents’ wealth, as well as the amount of (both on-shore and offshore) taxes they pay. Nonetheless, such basic information is not published by countries participating in the CRS. This situation is particularly problematic in terms of governments’ accountability and of public policy assessment. No government could claim victory over unemployment, without publishing detailed employment statistics by sector.

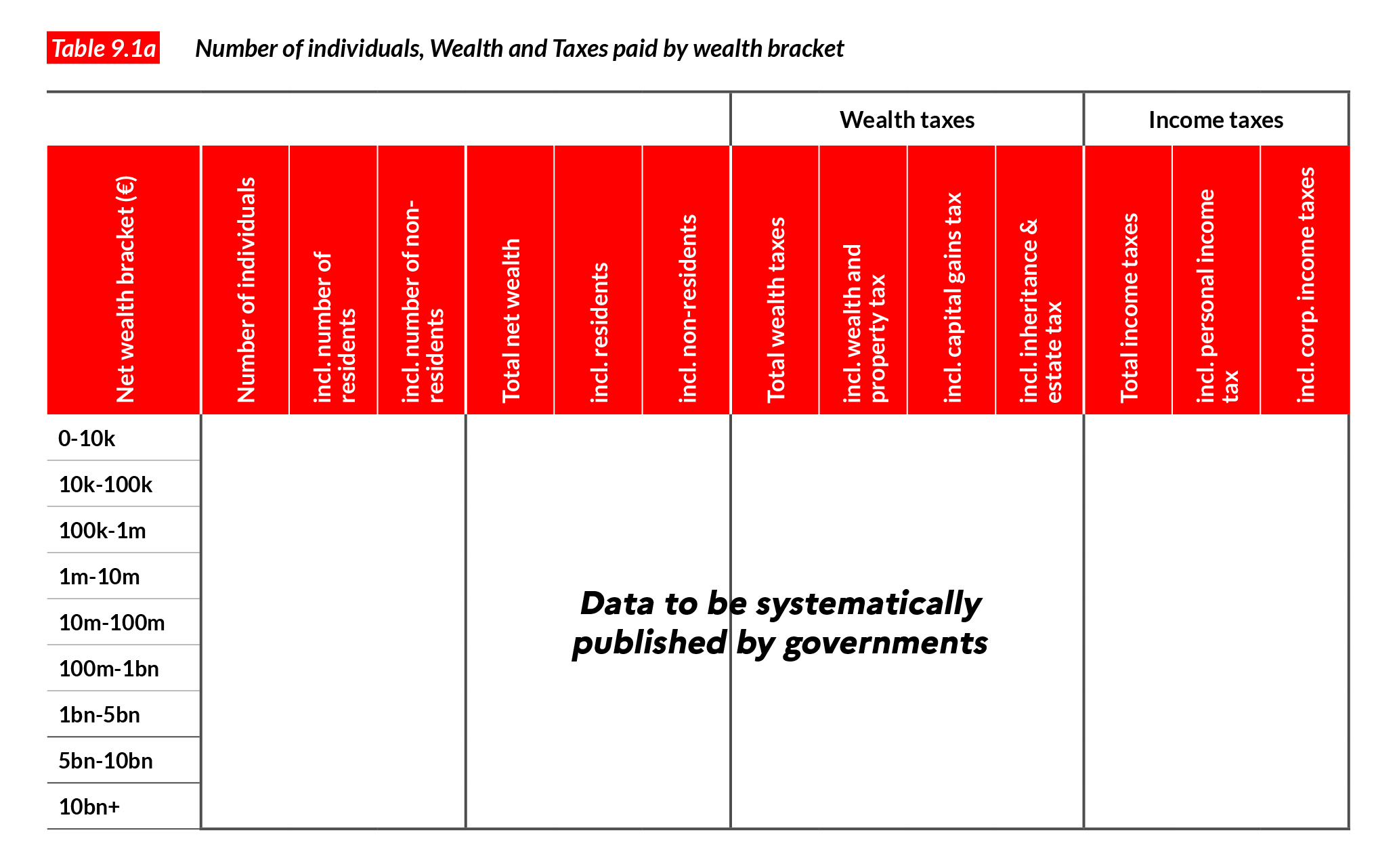

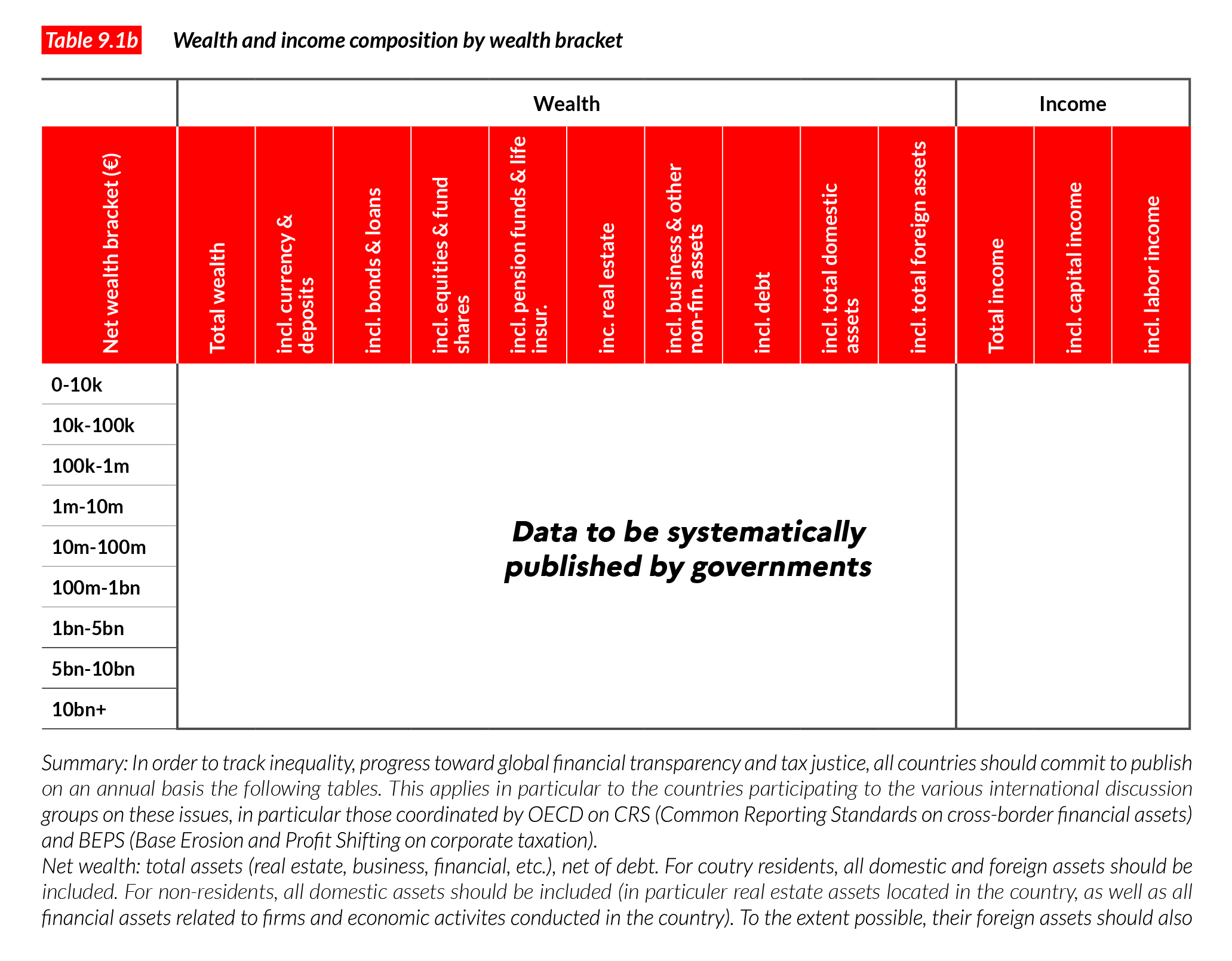

To properly assess progress in the fight against tax evasion, governments across the world should publicly release annual data on how many taxpayers there are in each income and wealth tax bracket and how much taxes they pay. Should the CRS work effectively, such information would be easily available. Table 9.1AB below shows the case of wealth (a similar table should be published for income), with different wealth and income tax brackets. For each of these brackets, tax authorities should publish information related to the number of individuals and the breakdown of their income, wealth and other taxes.

Towards a global asset register

Publishing basic information regarding tax transparency will certainly contribute to assessing the effectiveness of CRS or FATCA initiatives and can help to improve them. Putting an end to tax evasion across the world will however require more than the CRS or FATCA.

As a matter of fact, many tax havens and offshore financial institutions do not have incentives to provide accurate information, as they do not face large enough sanctions for non- or poor compliance. In addition, a large and growing fraction of offshore wealth is held by intertwined shell companies, trusts, and foundations, which disconnect assets from their actual owners. This makes it easy for offshore banks to falsely claim that they do not have any European, American, or Asian clients—while in fact such individuals are the beneficial owners of the assets held by the very same shell companies.

Therefore, the best way to end tax evasion across the world is to establish a global financial register. It would allow tax and

regulatory agencies to check if taxpayers properly report assets and capital income regardless of whatever information offshore financial institutions are willing to provide tax authorities. It would also allow governments to close corporate tax loopholes by enforcing a fair distribution of tax revenue globally for corporations with increasingly complex overseas operations. A global financial register could also serve as the informational basis for creating of a global wealth tax. Establishing such a register would not, however, mean that asset ownership would be disclosed to the general public. Such information could remain confidential in the same way as current income tax data is kept confidential.

Drawing up a global financial register would in fact be facilitated by the above- mentioned CRS and FATCA. It would however also provide additional sources of crucial financial information, gathered by (mostly private) financial institutions known as Central Securities Depositories (CSD). CSDs are the bookkeepers of equities and bonds issued by corporations and governments. They can maintain accounts as end-investor segregated accounts—which is the most transparent model, as it connects an individual to an asset. Or they can maintain omnibus accounts—a less transparent model, given that assets held by different investors are lumped into a single account under the name of a financial intermediary, making it difficult to identify end-investors. (See Box 9.1)

One key issue with using CSDs as the building block of a global financial register is that omnibus accounts prevail in most large western markets. (The Depository Trust Company in the United States and Clearstream in Europe, for instance, operate with omnibus accounts.) However, technical solutions facilitated by developments in information technologies already exist to allow for the identification of end asset holders in large western CSDs. Moreover, in certain countries such as Norway, or large emerging markets such as China and South Africa, CSDs operate through systems which allow for the identification of end asset owners. In short, creating a global financial register is not facing any insuperable technical problems, and groups of countries such as the European Union (and possibly the United States) could initiate the creation of such a register. The European Commission has recently launched a feasibility study for establishing such a register.

Towards a global asset register

This box draws upon Nougayrède’s work, the World Inequality Report 2018 and the World Inequality Database recent updates14,15,16.

In the modern financial system, shares and bonds issued by corporations no longer are paper certificates but electronic account entries. Holding chains are no longer direct—that is, they do not connect issuers directly with investors, but involve several intermediaries, often located in different countries. Central Securities Depositories (CSDs) are at the top of the chain, immediately after issuers. Their role is to record ownership of financial securities and sometimes handle transaction settlement. CSD clients are domestic financial institutions in the issuer country, foreign financial institutions, and other CSDs. After CSD participants, there are several other layers of financial intermediaries, and at the end of the chain comes a final intermediary; often a bank, which has a relationship with the investors in question.

Because so many intermediaries are involved, issuers of financial securities are disconnected from end-investors; public companies that issue securities no longer know who their shareholders or bondholders are. CSDs, as a part of the chain of financial intermediation, both enable and blur this relationship. The system was not intentionally designed for anonymity, but it has evolved in this way over the years because of how complex regulations are cross-border securities trading. The evolution towards non-transparency has also been fostered by the fact that this is a highly technical topic and that it has drawn limited attention among the media or public opinion over the past few years.

Non-transparent accounts prevail in most western CSDs.

There are two broad types of accounts in the CSD world. “Segregated accounts” allow one to hold securities in distinct accounts, opened in the name of the individual end- investors. Consequently, this model allows

for transparency. The opposite model is that of “omnibus accounts” (or in the USA, “street name registration”) where securities belonging to several investors are pooled together into one account under the name of a single account-holder, usually a financial intermediary, thereby blurring end-investors’ identity.

One of the key issues for drawing up a global financial register is that non-transparent accounting (that is, “omnibus accounts”) prevails in most western markets. For instance, the US CSD, the Depository Trust Company (DTC), uses omnibus accounts. In its books, the DTC only identifies brokerage firms and other intermediaries, but not the end owners of US stocks and bonds. “Omnibus accounts” also prevail in most European countries—in particular, within Euroclear and Clearstream CSDs. This makes it difficult to compile a global financial register based on existing western CSDs.

However, more transparency is possible.

More transparency within western CSDs can however be envisioned. The current system creates a number of risks for the financial industry, of which it is very much aware. In 2014, Clearstream Banking in Luxembourg agreed upon a $152 million settlement with the US Treasury, following allegations that it held $2.8 billion in US securities in an omnibus account for the benefit of the Central Bank of Iran, which was subject to US sanctions. As a result, the securities industry has been discussing a number of options which could be put in place to allow for greater transparency of information on end- investors. These might include discontinuing the use of omnibus accounts and introducing new information transfer standards (as is done in the payments industry) or ex-post audit trails, which would enable information on the identity of the end beneficiary of financial transactions to circulate throughout the chain. New technologies (such as blockchain) could also enhance traceability.

In fact, transparent market infrastructures already exist today in both high income and emerging countries. In Norway, the CSD lists all individual shareholders in domestic companies, acts as formal corporate registrar, and reports back directly to tax authorities while protecting them. In China, the China Securities Depository Clearing Corporation Limited (“Chinaclear”) operates a fully transparent system for shares issued by Chinese companies and held by domestic Chinese investors. At the end of 2015, it held $8 trillion worth of securities in custody, roughly the size of the CSDs in France, Germany, and the UK, and maintained securities accounts for 99 million end- investors. Some segregation functionalities already exist within some of the larger western CSDs (like DTC or Euroclear), and could be expanded. Many believe that segregated CSD accounting would push for better corporate governance by giving a greater voice to small investors. All of this suggests that more could be done in large western CSDs to introduce greater investor transparency.

1 Zucman, G. 2015. “The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens,” The University of Chicago Press.

2 Zucman, G. 2014. “Taxing across borders: Tracking personal wealth and corporate profits.” Journal of economic perspectives 28, no. 4: 121-48.

3 Saez, E. and G. Zucman. 2019. “The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make them Pay.” New York: W. W. Norton.

4 Baraké, Mona, P.-E. Chouc, T. Neef and G. Zucman. 2021. “Collecting the Tax Deficit of Multinational Companies: Simulations for the European Union.” EU Tax Observatory Report n°1.

5 Baraké et al. “Collecting the Tax Deficit of Multinational Companies”.

6 Baraké et al. “Collecting the Tax Deficit of Multinational Companies”

7 Baraké et al. “Collecting the Tax Deficit of Multinational Companies”

8 Baraké et al. “Collecting the Tax Deficit of Multinational Companies”

9 Chiochetti, A. 2020. “The effect of automatic exchange of information on evaded wealth”, PSE Master Thesis, 2020;

Zucman, G. 2013. “The Missing Wealth of Nations”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics.

10 See for e.g. Michel, A. 7 June 2019. “L’OCDE constate une importante décrue des dépôts bancaires dans les paradis fiscaux”. Le Monde: They noted an “important reduction of bank deposits in tax havens”. Unfortunately, deposits only represent a small fraction (5-10%) of assets held in tax havens, and a reduction in deposits can mask an increase in other forms of assets.

11 The Financial Secrecy Index is available here https://fsi.taxjustice.net/en/. It is published by the Tax Justice Network and complements the Inequality Transparency Index published by the World Inequality Lab on WID.world.

12 Casi-Eberhard, E., C. Spengel and B. Stage. 2019. Cross-Border Tax Evasion after the Common Reporting Standard: Game Over? ZEW-Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper, 18-036.

13 To address this issue, the OECD took steps in 2017 to counter asset shifting to US banks, by including in reporting FIs entities which advise their clients to open a bank account in non-reporting jurisdictions, and continue to do so.

14 Nougayrède, D. 2017. “Towards Global Financial Register? The Case for End Investor Transparency in Central Securities Depositories”. Journal of Financial Regulation; See Alvaredo, F., L. Chancel, T. Piketty, E. Saez, G. Zucman. 2018. World Inequality Report 2018, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

15 See Alvaredo et al. World Inequality Report 2018.

16 See World Inequality Database: www.wid.world