Reliable inequality data as a global public good

We live in a data-abundant world and yet we lack basic information about inequality. Economic growth numbers are published every year by governments across the globe, but they do not tell us about how growth is distributed across the population – about who gains and who loses from economic policies. Accessing such data is critical for democracy. Beyond income and wealth, it is also critical to improve our collective capability to measure and monitor other dimensions of socio- economic disparities, including gender and environmental inequalities. Open-access, transparent, reliable inequality information is a global public good.

This report presents the most up-to-date synthesis of international research efforts to track global inequalities. The data and analysis presented here are based on the work of more than 100 researchers over four years, located on all continents, contributing to the World Inequality Database (WID.world), maintained by the World Inequality Lab. This vast network collaborates with statistical institutions, tax authorities, universities and international organizations, to harmonize, analyze and disseminate comparable international inequality data.

Contemporary income and wealth inequalities are very large

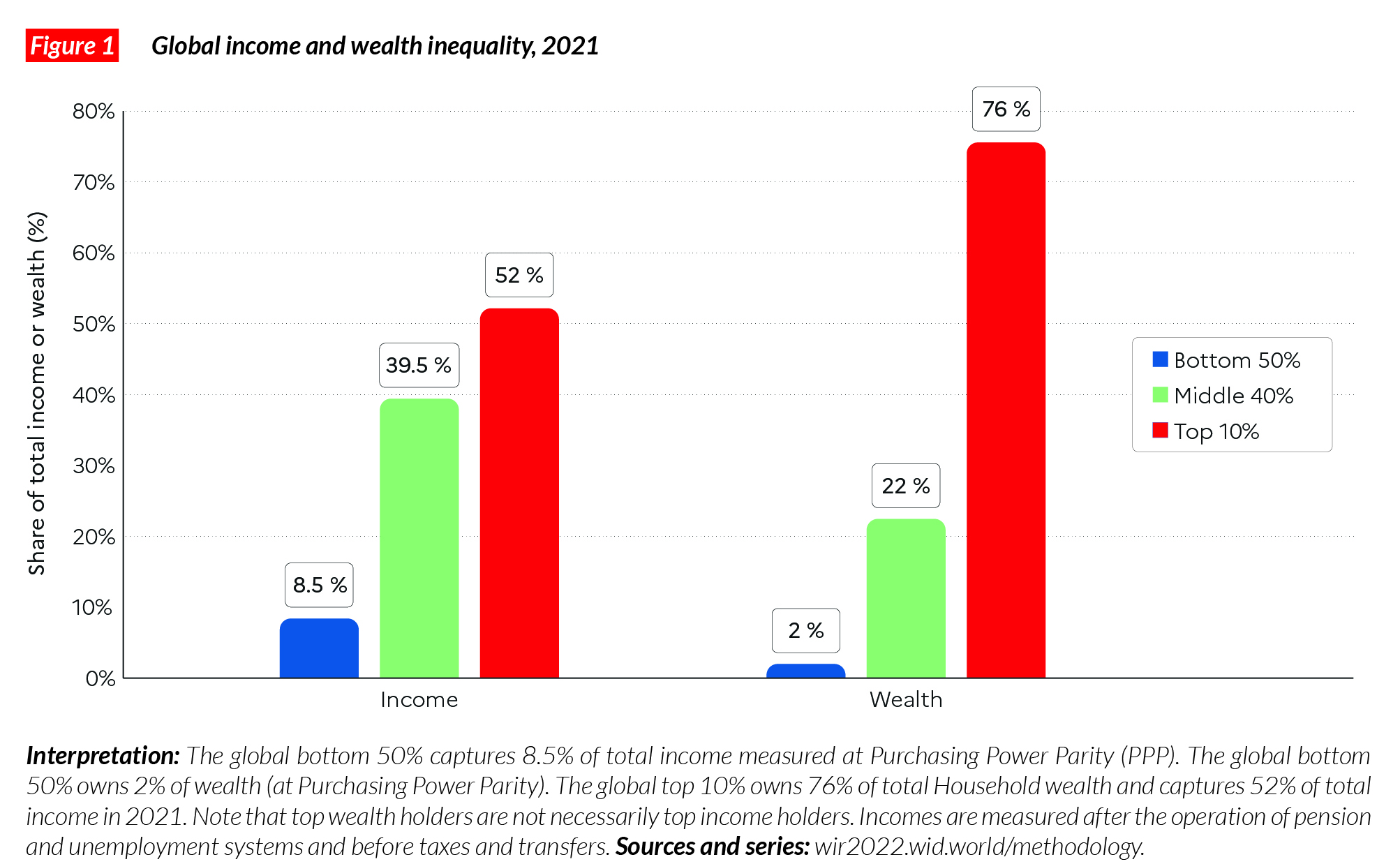

An average adult individual earns PPP €16,700 (PPP USD23,380) per year in 2021, and the average adult owns €72,900 (USD102,600)1.1 These averages mask wide disparities both between and within countries. The richest 10% of the global population currently takes 52% of global income, whereas the poorest half of the population earns 8.5% of it. On average, an individual from the top 10% of the global income distribution earns €87,200 (USD122,100) per year, whereas an individual from the poorest half of the global income distribution makes €2,800 (USD3,920) per year (Figure 1).

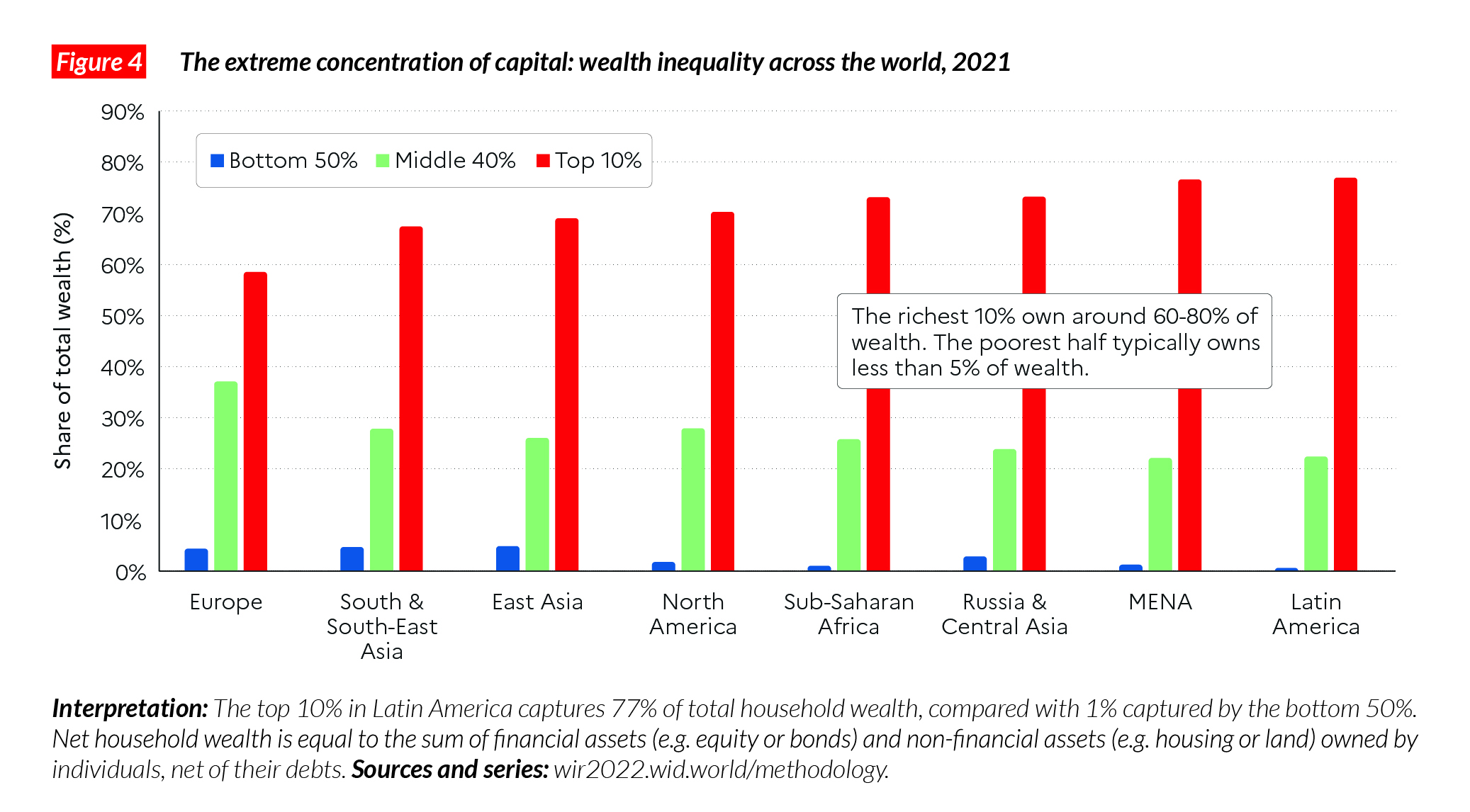

Global wealth inequalities are even more pronounced than income inequalities. The poorest half of the global population barely owns any wealth at all, possessing just 2% of the total. In contrast, the richest 10% of the global population own 76% of all wealth. On average, the poorest half of the population owns PPP €2,900 per adult, i.e. USD4,100 and the top 10% own €550,900 (or USD771,300) on average.

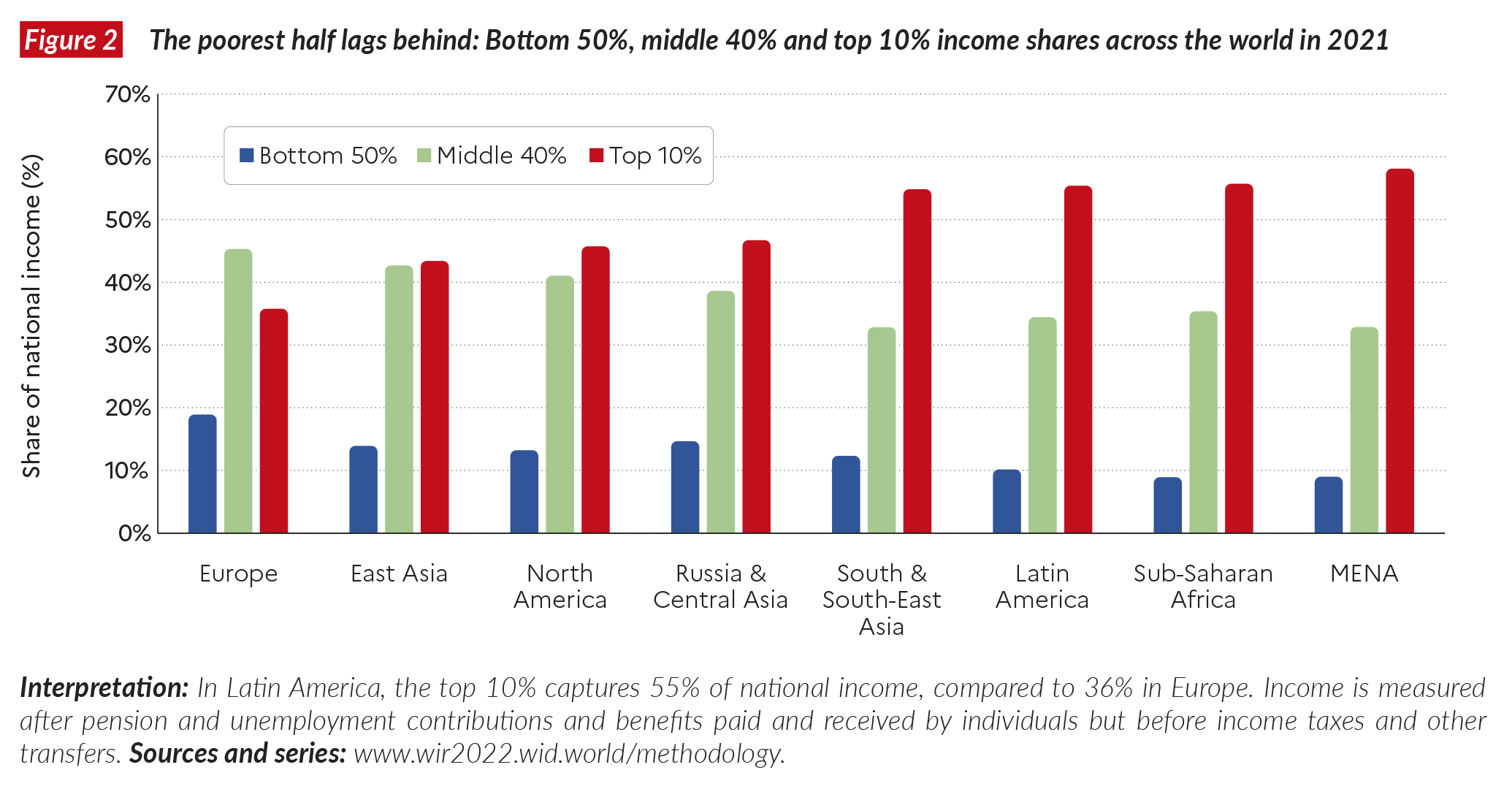

“MENA” is the most unequal region in the world, Europe has the lowest inequality levels

Figure 2 shows income inequality levels across the regions. Inequality varies significantly between the most equal region (Europe) and the most unequal (Middle East and North Africa i.e. “MENA”). In Europe, the top 10% income share is around 36%, whereas in “MENA” it reaches 58%. In between these two levels, we see a diversity of patterns. In East Asia, the top 10% makes 43% of total income and in Latin America, 55%.

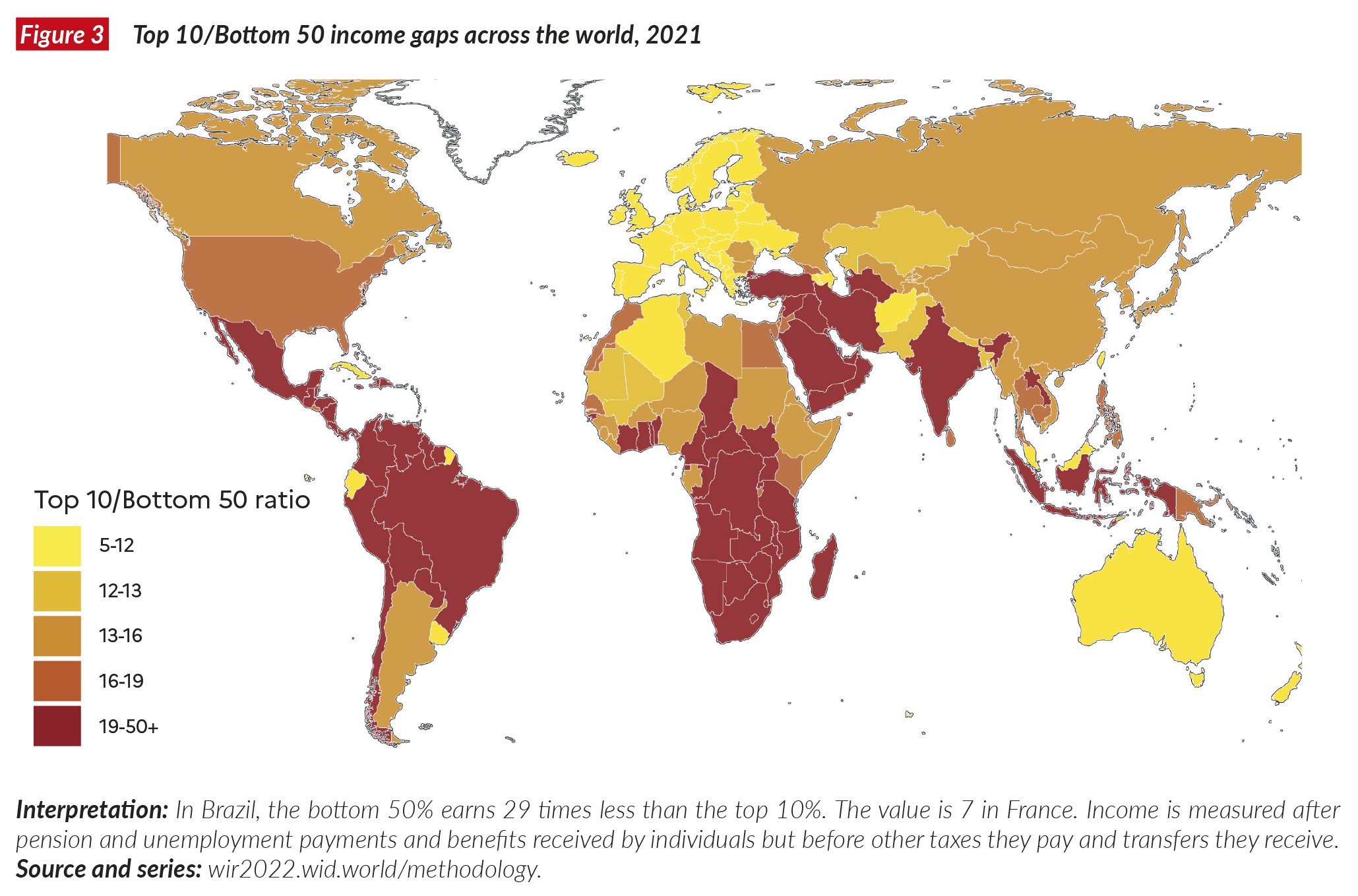

Average national incomes tell us little about inequality

The world map of inequalities (Figure 3) reveals that national average income levels are poor predictors of inequality: among high-income countries, some are very unequal (such as the US), while other are relatively equal (e.g. Sweden). The same is true among low- and middle-income countries, with some exhibiting extreme inequality (e.g. Brazil and India), somewhat high levels (e.g. China) and moderate to relatively low levels (e.g. Malaysia, Uruguay).

Inequality is a political choice, not an inevitability

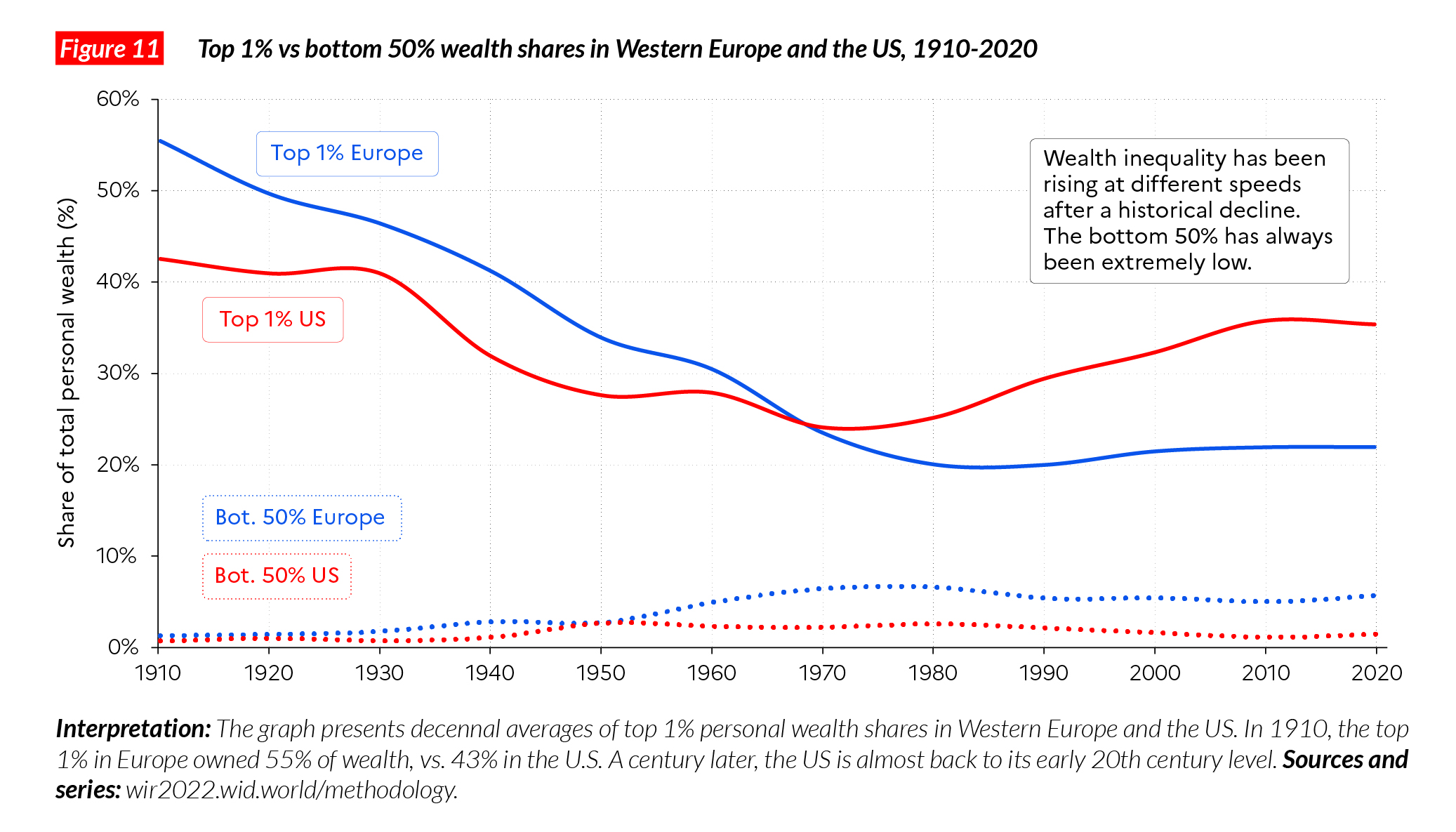

Income and wealth inequalities have been on the rise nearly everywhere since the 1980s, following a series of deregulation and liberalization programs which took different forms in different countries. The rise has not been uniform: certain countries have experienced spectacular increases in inequality (including the US, Russia and India) while others (European countries and China) have experienced relatively smaller rises. These differences, which we discussed at length in the previous edition of the World Inequality Report, confirm that inequality is not inevitable, it is a political choice2.

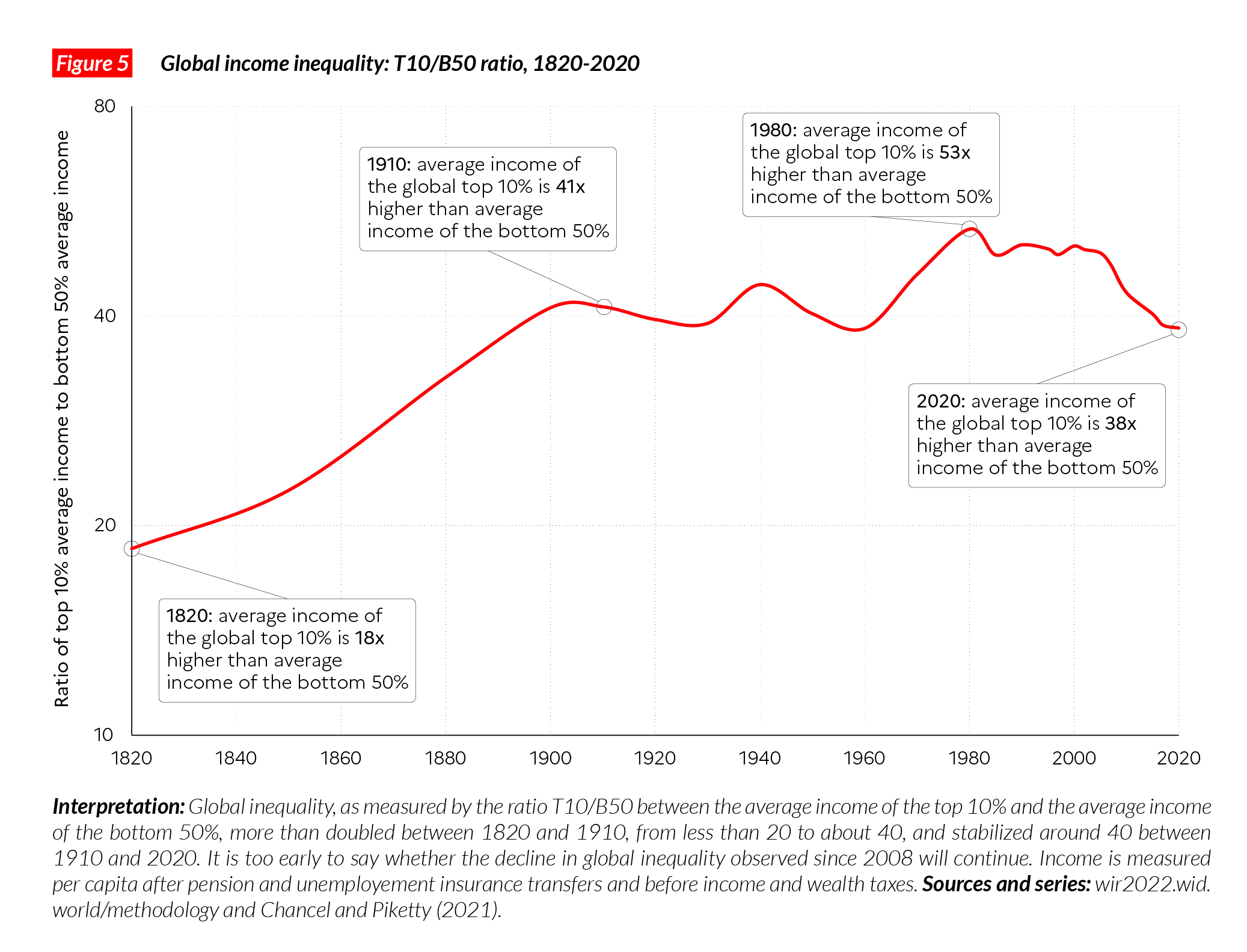

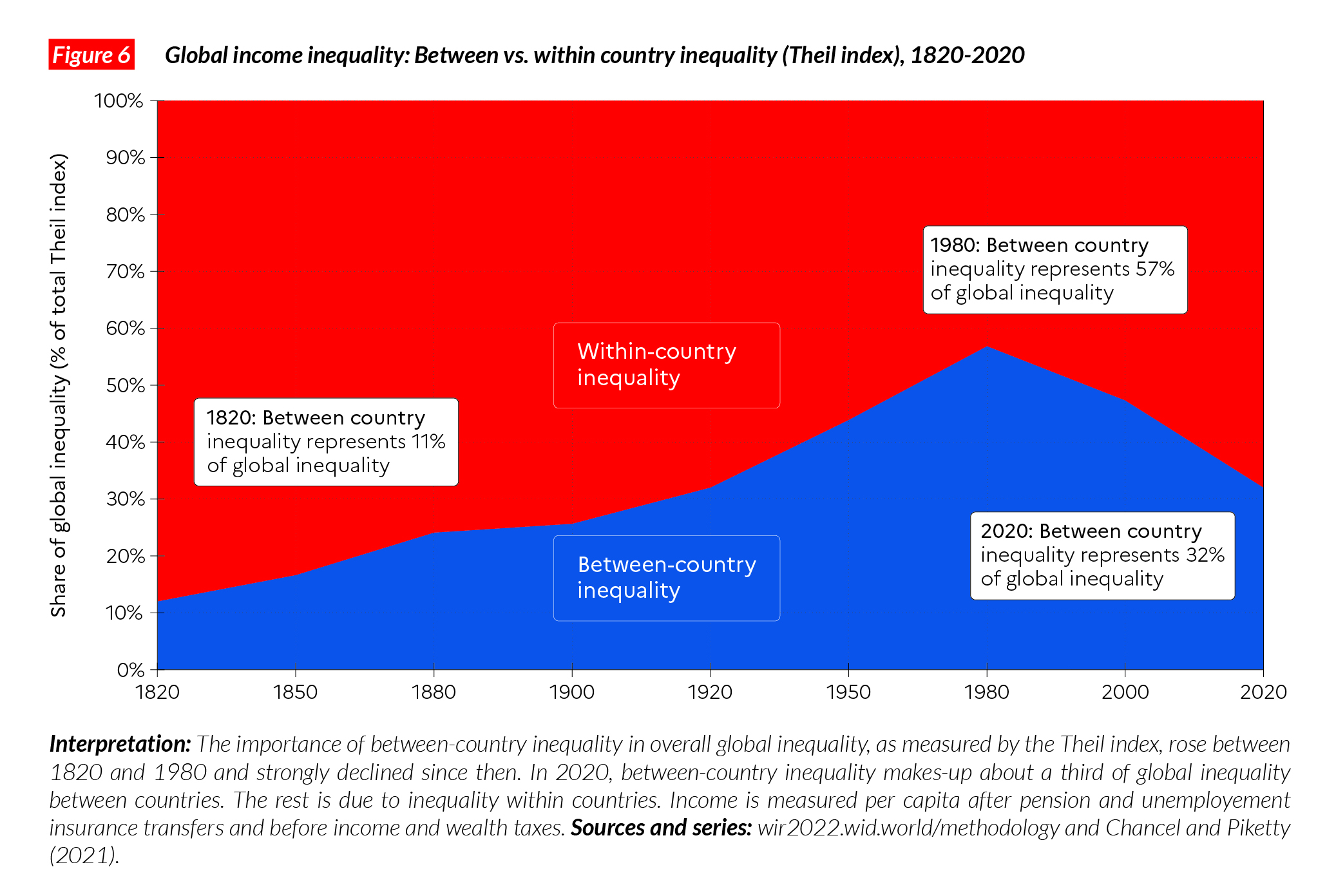

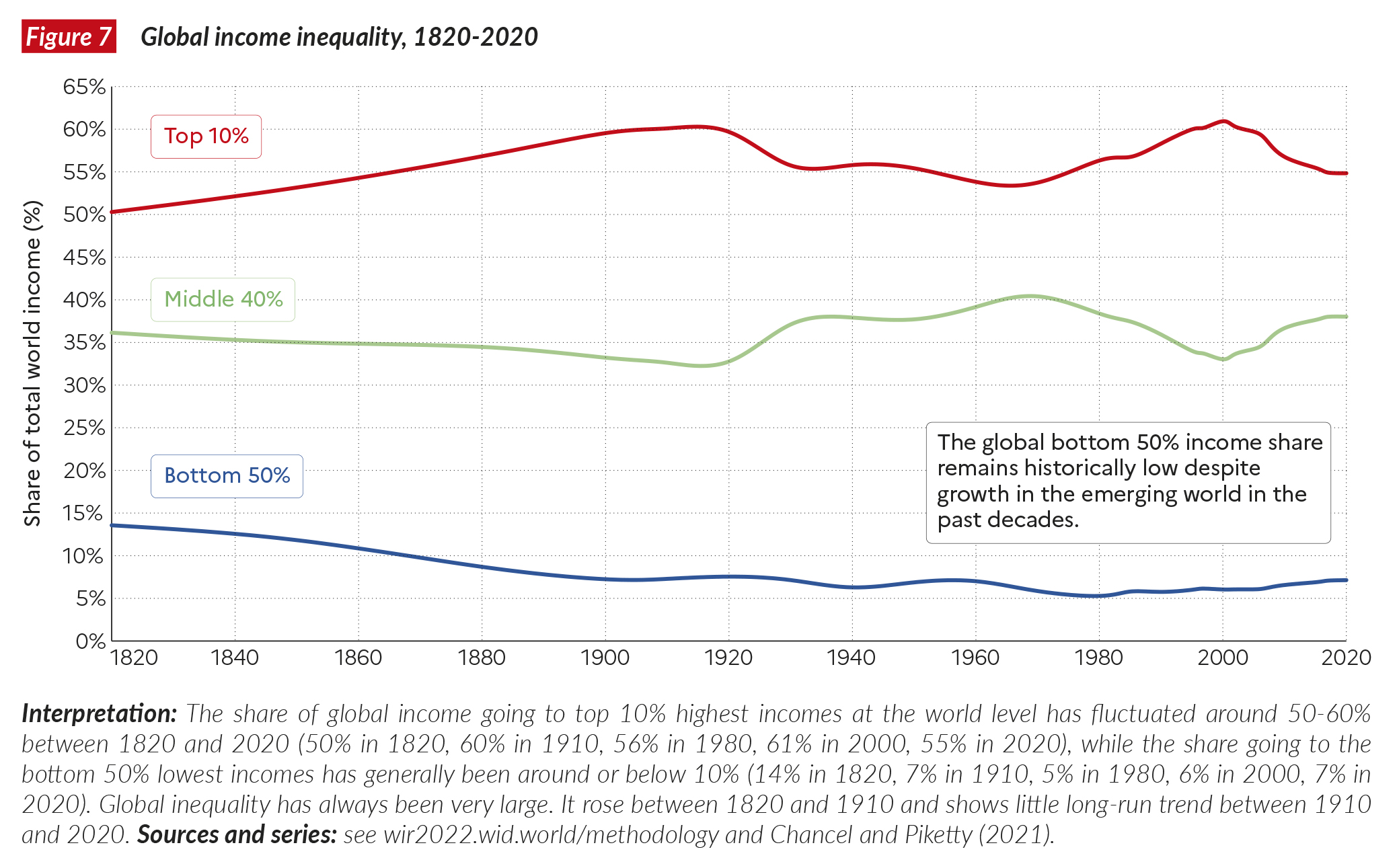

Contemporary global inequalities are close to early 20th century levels, at the peak of Western imperialism

While inequality has increased within most countries, over the past two decades, global inequalities between countries have declined. The gap between the average incomes of the richest 10% of countries and the average incomes of the poorest 50% of countries dropped from around 50x to a little less than 40x (Figure 5). At the same time, inequalities increased significantly within countries. The gap between the average incomes of the top 10% and the bottom 50% of individuals within countries has almost doubled, from 8.5x to 15x (see Chapter 2).This sharp rise in within country inequalities has meant that despite economic catch-up and strong growth in the emerging countries, the world remains particularly unequal today. It also means that inequalities within countries are now even greater than the significant inequalities observed between countries (Figure 6).

Global inequalities seem to be about as great today as they were at the peak of Western imperialism in the early 20th century. Indeed, the share of income presently captured by the poorest half of the world’s people is about half what it was in 1820, before the great divergence between Western countries and their colonies (Figure 7). In other words, there is still a long way to go to undo the global economic inequalities inherited from the very unequal organization of world production between the mid-19th and mid- 20th centuries.

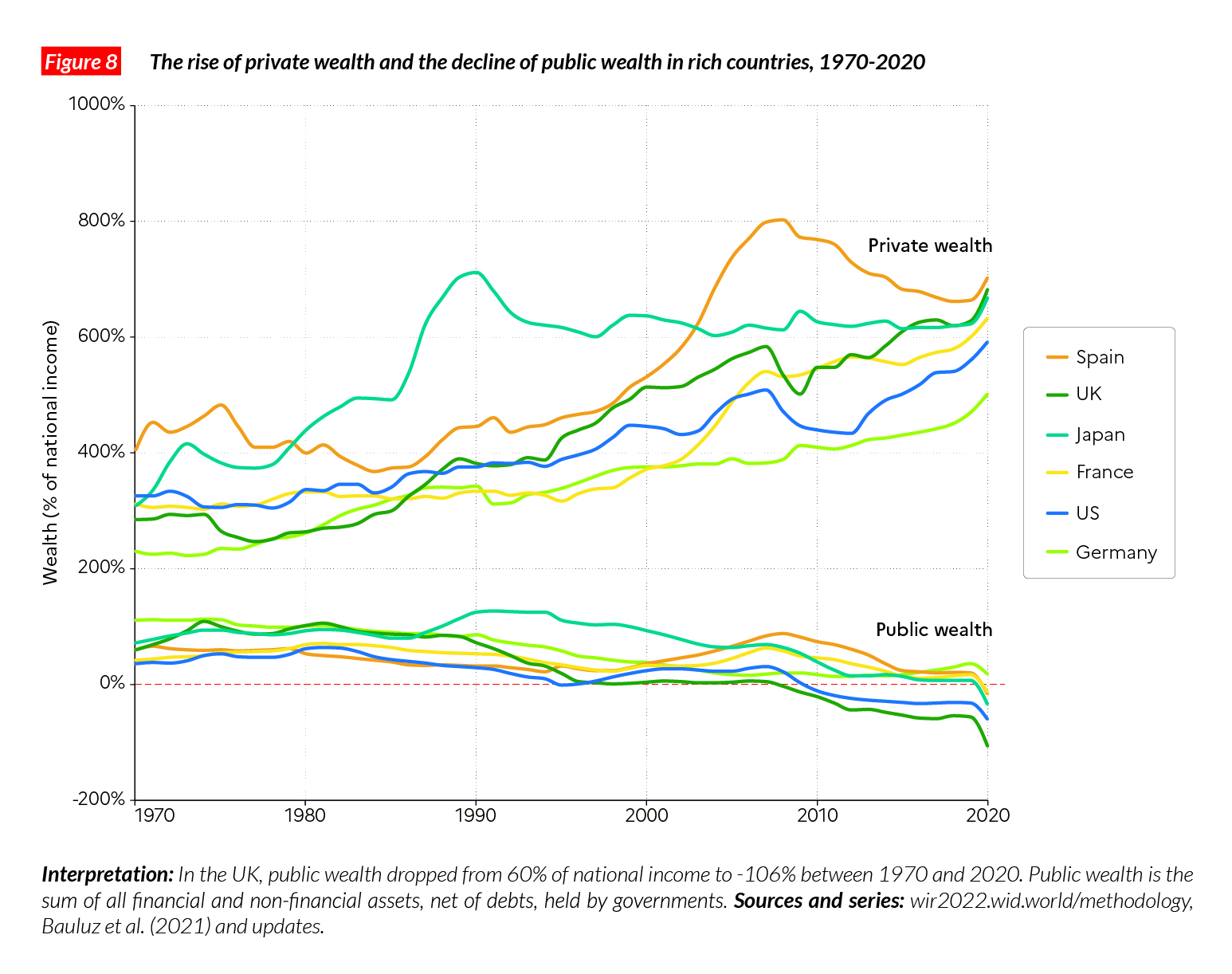

Nations have become richer, but governments have become poor

One way to understand these inequalities is to focus on the gap between the net wealth of governments and net wealth of the private sector. Over the past 40 years, countries have become significantly richer, but their governments have become significantly poorer. The share of wealth held by public actors is close to zero or negative in rich countries, meaning that the totality of wealth is in private hands (Figure 8). This trend has been magnified by the Covid crisis, during which governments borrowed the equivalent of 10-20% of GDP, essentially from the private sector. The currently low wealth of governments has important implications for state capacities to tackle inequality in the future, as well as the key challenges of the 21st century such as climate change.

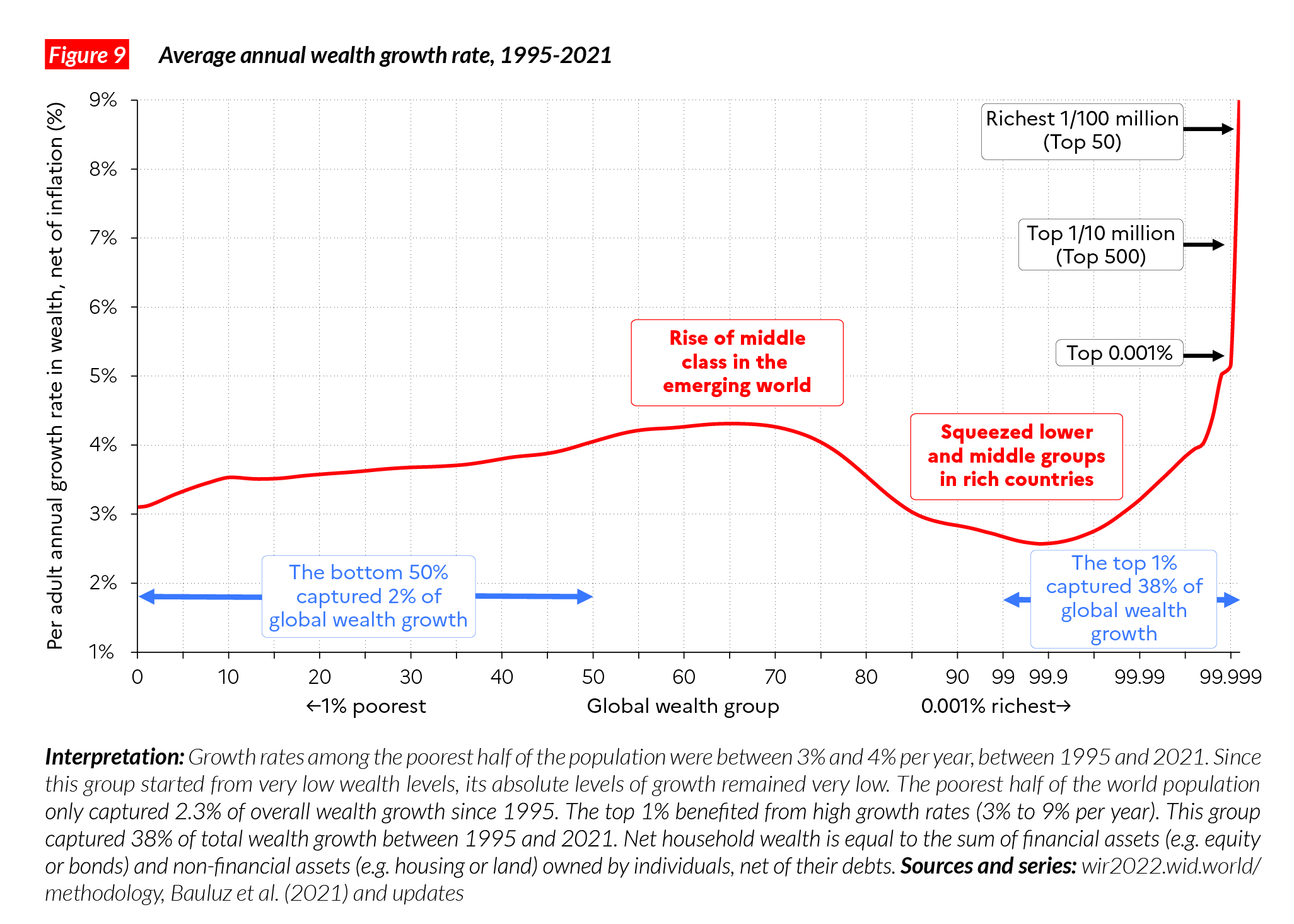

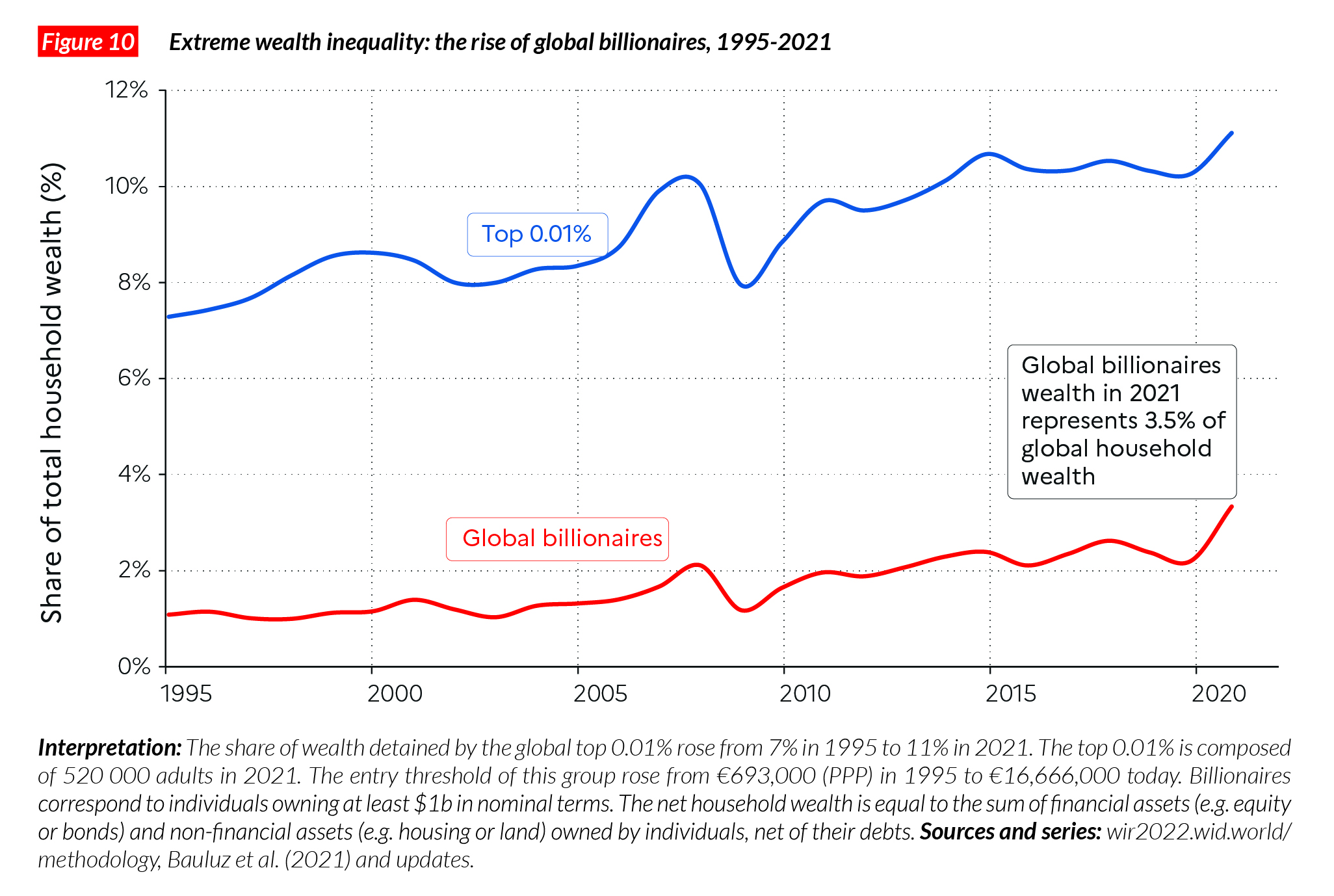

Wealth inequalities have increased at the very top of the distribution

The rise in private wealth has also been unequal within countries and at the world level. Global multimillionaires have captured a disproportionate share of global wealth growth over the past several decades: the top 1% took 38% of all additional wealth accumulated since the mid-1990s, whereas the bottom 50% captured just 2% of it. This inequality stems from serious inequality in growth rates between the top and the bottom segments of the wealth distribution. The wealth of richest individuals on earth has grown at 6 to 9% per year since 1995, whereas average wealth has grown at 3.2% per year (Figure 9). Since 1995, the share of global wealth possessed by billionaires has risen from 1% to over 3%. This increase was exacerbated during the COVID pandemic. In fact, 2020 marked the steepest increase in global billionaires’ share of wealth on record (Figure 10).

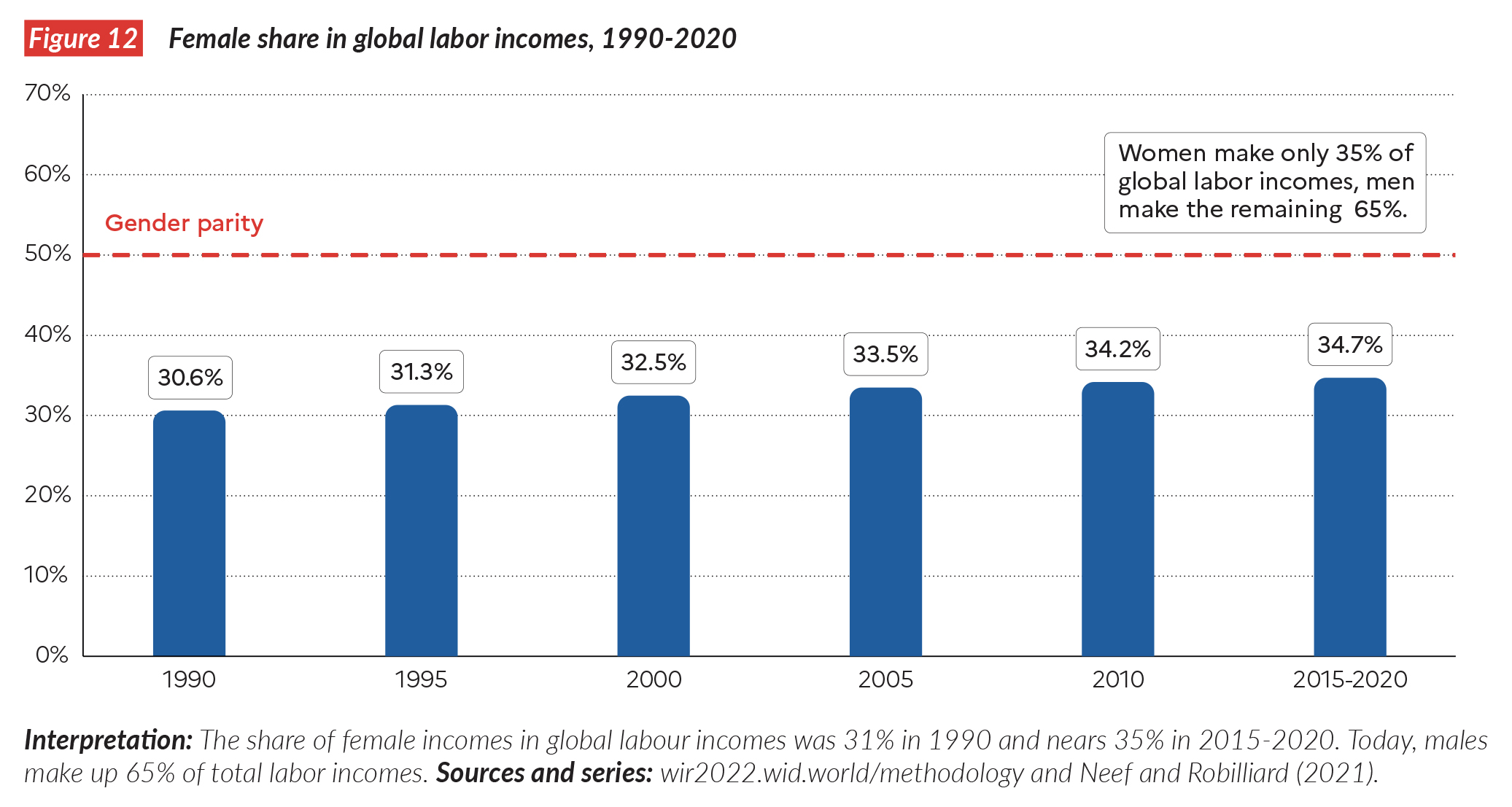

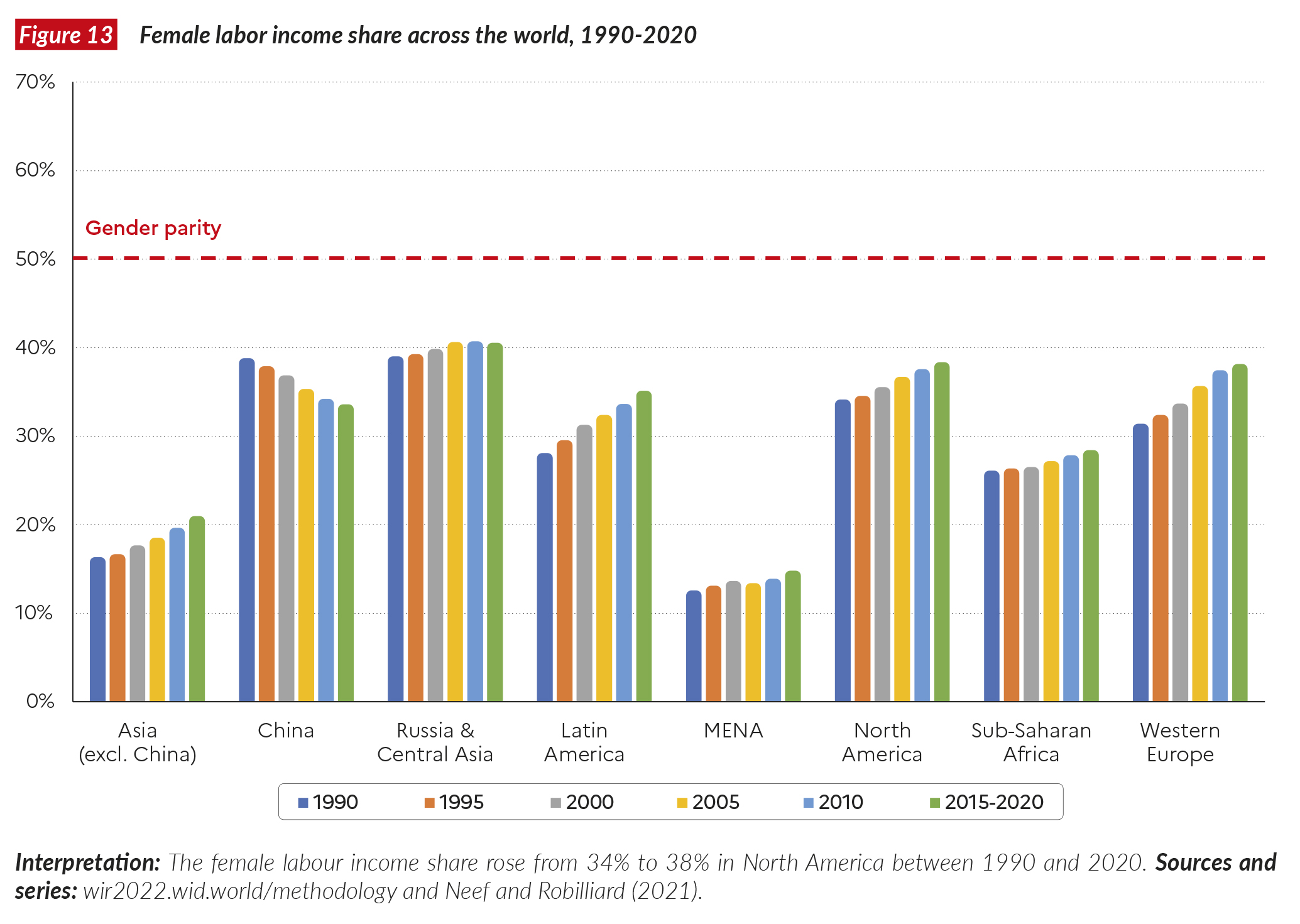

Gender inequalities remain considerable at the global level, and progress within countries is too slow

The World Inequality Report 2022 provides the first estimates of the gender inequality in global earnings. Overall, women’s share of total incomes from work (labor income) neared 30% in 1990 and stands at less than 35% today (Figure 12). Current gender earnings inequality remains very high: in a gender equal world, women would earn 50% of all labor income. In 30 years, progress has been very slow at the global level, and dynamics have been different across countries, with some recording progress but others seeing reductions in women’s share of earnings (Figure 13).

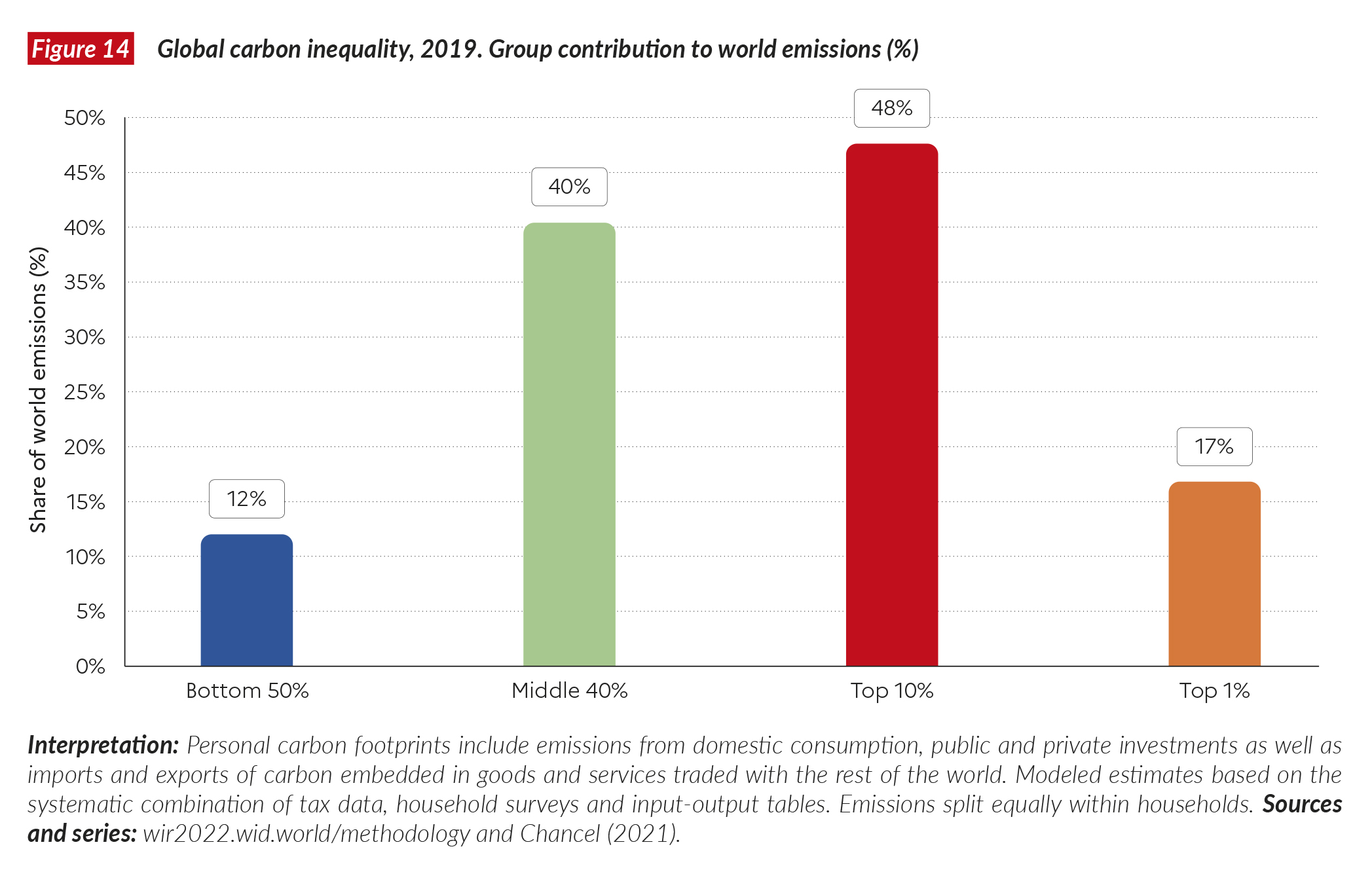

Addressing large inequalities in carbon emissions is essential for tackling climate change

Global income and wealth inequalities are tightly connected to ecological inequalities and to inequalities in contributions to climate change. On average, humans emit 6.6 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2) per capita, per year. Our novel data set on carbon emissions inequalities reveals important inequalities in CO2 emissions at the world level: the top 10% of emitters are responsible for close to 50% of all emissions, while the bottom 50% produce 12% of the total (Figure 14).

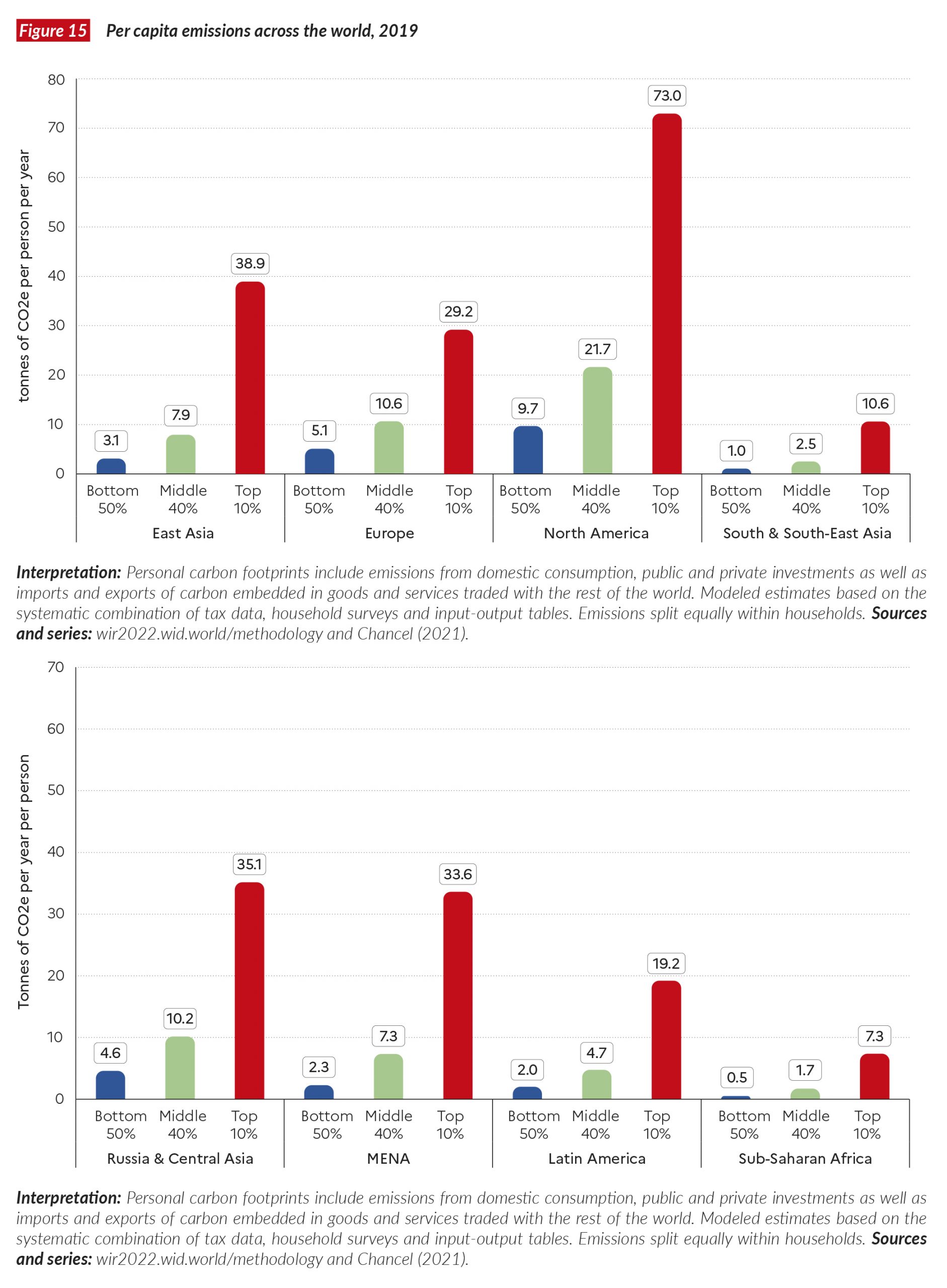

Figure 15 shows that these inequalities are not just a rich vs. poor country issue. There are high emitters in low- and middle-income countries and low emitters in rich countries. In Europe, the bottom 50% of the population emits around five tonnes per year per person; the bottom 50% in East Asia emits around three tonnes and the bottom 50% in North America around 10 tonnes. This contrasts sharply with the emissions of the top 10% in these regions (29 tonnes in Europe, 39 in East Asia, and 73 in North America).

This report also reveals that the poorest half of the population in rich countries is already at (or near) the 2030 climate targets set by rich countries, when these targets are expressed on a per capita basis. This is not the case for the top half of the population. Large inequalities in emissions suggest that climate policies should target wealthy polluters more. So far, climate policies such as carbon taxes have often disproportionately impacted low- and middle-income groups, while leaving the consumption habits of wealthiest groups unchanged.

Redistributing wealth to invest in the future

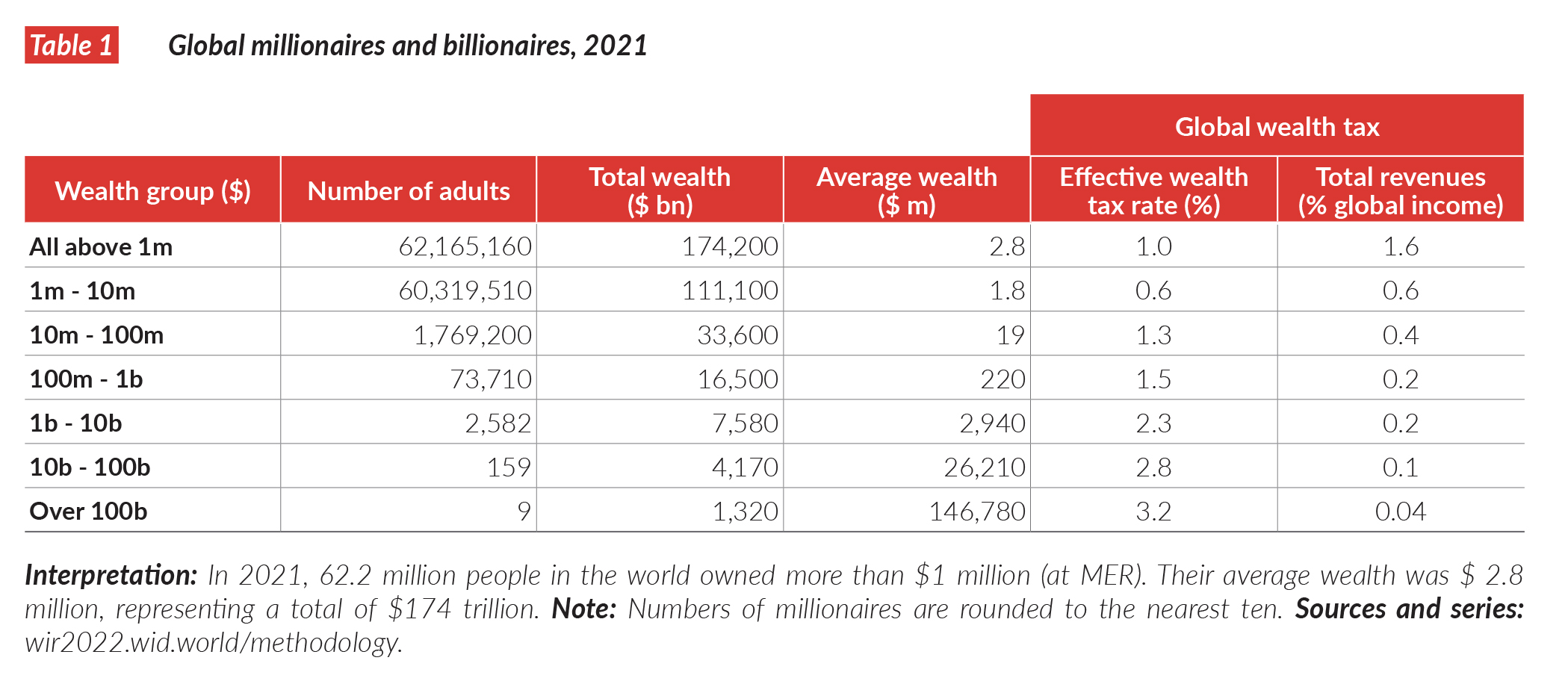

The World Inequality Report 2022 reviews several policy options for redistributing wealth and investing in the future in order to meet the challenges of the 21st century. Table 1 presents revenue gains that would come from a modest progressive wealth tax on global multimillionaires. Given the large volume of wealth concentration, modest progressive taxes can generate significant revenues for governments. In our scenario, we find that 1.6% of global incomes could be generated and reinvested in education, health and the ecological transition. The report comes with an online simulator so that everybody can design their preferred wealth tax at the global level, or in their region.

We stress at the outset that addressing the challenges of the 21st century is not feasible without significant redistribution of income and wealth inequalities. The rise of modern welfare states in the 20th century, which was associated with tremendous progress in health, education, and opportunities for all (see Chapter 10), was linked to the rise of steep progressive taxation rates. This played a critical role in order to ensure the social and political acceptability of increased taxation and socialization of wealth. A similar evolution will be necessary in order to address the challenges of the 21st century. Recent developments in international taxation show that progress towards fairer economic policies is indeed possible at the global level as well as within countries. Chapters 8, 9 and 10 of the report discuss various options to tackle inequality, learning from examples all over the world and throughout modern history. Inequality is always political choice and learning from policies implemented in other countries or at other points of time is critical to design fairer development pathways.

1Values expressed at Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). The Concept of income used is national income (i.e. the total income in the world) and the concept of wealth used is that of of household wealth. In this report, we will also use another concept of wealth: net national wealth (this is household wealth to which we add public wealth and wealth from non-profit sector). The average national wealth is €98,600 (USD139,000).

2 World Inequality Report 2018, Harvard University Press, and online at wir2018.wid.world